|

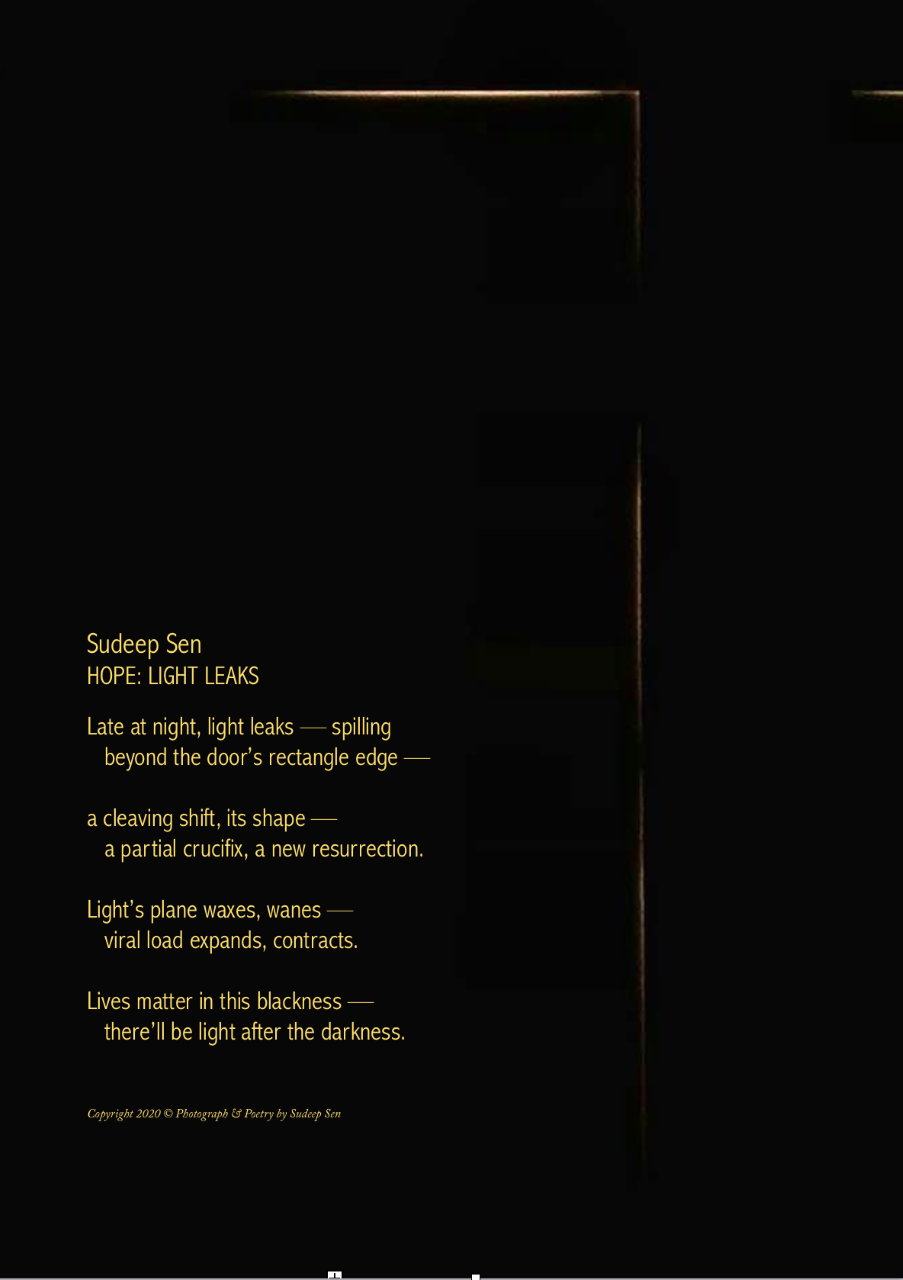

Sudeep Sen’s [www.sudeepsen.org] prize-winning books include: Postmarked India: New & Selected Poems (HarperCollins), Rain, Aria (A. K. Ramanujan Translation Award), Fractals: New & Selected Poems | Translations 1980-2015 (London Magazine Editions), EroText (Vintage: Penguin Random House), and Kaifi Azmi: Poems | Nazms (Bloomsbury). He has edited influential anthologies, including: The HarperCollins Book of English Poetry (editor), World English Poetry, and Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians (Sahitya Akademi). Blue Nude: Anthropocene, Ekphrasis & New Poems (Jorge Zalamea International Poetry Prize) and The Whispering Anklets are forthcoming. Sen’s works have been translated into over 25 languages. His words have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, Newsweek, Guardian, Observer, Independent, Telegraph, Financial Times, Herald, Poetry Review, Literary Review, Harvard Review, Hindu, Hindustan Times, Times of India, Indian Express, Outlook, India Today, and broadcast on bbc, pbs, cnn ibn, ndtv, air & Doordarshan. Sen’s newer work appears in New Writing 15 (Granta), Language for a New Century (Norton), Leela: An Erotic Play of Verse and Art (Collins), Indian Love Poems (Knopf/Random House/Everyman), Out of Bounds (Bloodaxe), Initiate: Oxford New Writing (Blackwell), and Name me a Word (Yale). He is the editorial director of AARK ARTS and the editor of Atlas. Sen is the first Asian honoured to deliver the Derek Walcott Lecture and read at the Nobel Laureate Festival. The Government of India awarded him the senior fellowship for “outstanding persons in the field of culture/literature.”

0 Comments