|

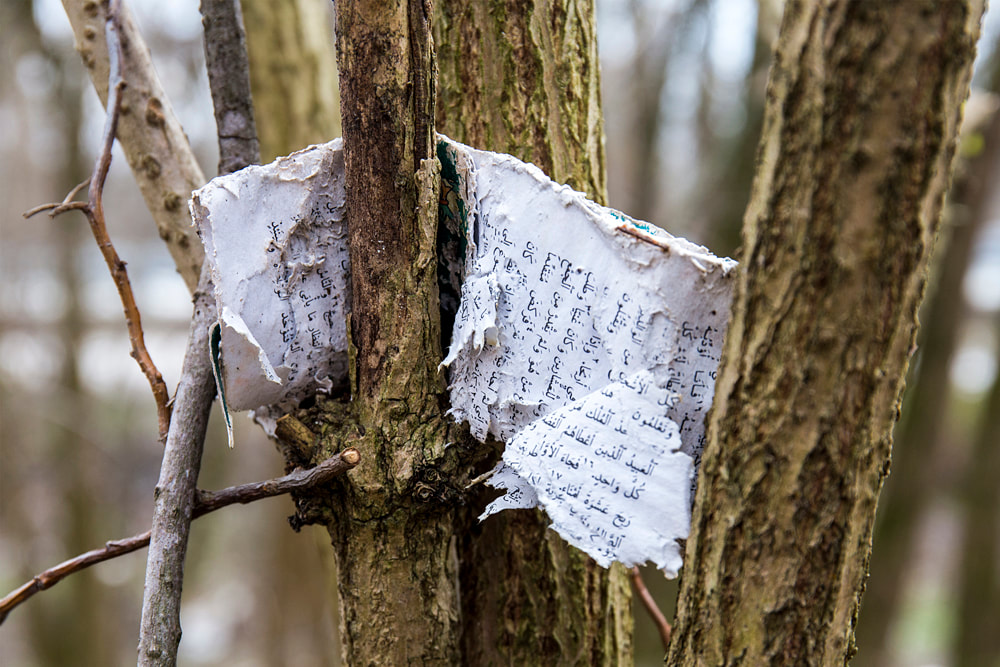

Tall, slim, moustachioed Mark Allboy took the flight from London to Kuala Lumpur. This was followed by a local flight descending from out of a brightening sky, bumping its wheels on the tarmac of Penang airport. For Mark it was almost a spiritual moment. Silhouetted coconut trees, cloud-angels and sparkling winged birds seemed to bring the mercy of arrival to this tentative traveller. The oven blast of air on exiting the craft, however, was a rude awakening. Uncomfortable moisture ran down Mark’s back, dampening his arms. His friend, Antony Mudaliyar was waiting as Mark exited customs. ‘How's the flight, any descent stewardesses? It’s fan-bloody-tastic to see you. You look great. You must be tired,. How’s Blicton,? I’ve never been back. Do you ever see Cioffi? No I don’t suppose that you do, that was years ago, and that other lecturer, the one who was having all those affairs with the students'. Anthony waved his hand dangerously as he drove and talked on. ‘Rolf, that was his name wasn’t it.’ Anthony talked practically non-stop as he drove Mark straight into Penang’s Georgetown. There, Anthony bought Mark a Western breakfast with all the trimmings including (beef) bacon, Mark thought ‘beef bacon, what heresy is this’, then there were the minuscule fried eggs - American style sunny side up orangey/yellow, and fried, tasteless, tomato as well as cold, hard toast. What Mark really wanted, was his first real taste of exotic Malaysian cuisine! The food on his Malaysian air carrier didn't count. It was to be a pleasure deferred. In England, exuberant Antony had been just another well-tanned Britisher with Indian ancestry. They drank, talked about football, women and spent as little time as they could studying Sartre, Husserl and Heidegger. Together with three others, they were a multi-racial band of brothers, practically indistinguishable one from another, despite they all being from different countries and, some, different religions. It never mattered. In Anthony’s car, the first thing Mark noticed was the small statue of Ganesha (Ganapati – the elephant headed Hindu god) atop the dashboard. Another was the slightly old, and browning string of jasmine flowers hanging from the car’s mirror. Mark wanted to say something. Ask questions. He held back. They had only just met after five years. There would be plenty of time, he thought, for catch-ups, if the Muses were willing. They crossed the unruly Straits of Malacca. The 1920, turmeric tinctured, ferry rose and dipped from Penang Island to the mainland at Butterworth. Despite being tired from the long flight, Mark loved watching the white furling waves emerge from the rear of the ancient ferry, seeing them merge into perspective, disappear like so many of his youthful dreams and fancies. He raised his head, feeling the salty breeze on his cheeks, the smell of ozone in his nostrils and a brief sense of freedom unfettered from his life in the UK. Anthony drove inland from cluttered Butterworth, along windy roads, past the Australian Air Force base, past the green shooting paddy fields and the laboriously slow moving water buffalo. The journey both excited and exhausted Mark. He could feel Jet lag creeping, taking the edge off his experience. The cool of the car’s air-conditioning fought bravely with the mounting heat from outside. It almost won. The interior of the ageing Toyota Carina was a little warmer than cool, warm enough and cool enough to lull Mark to sleep. He dozed the last half-hour of the journey, missing the small town of Sungai Petani and the small shrine to Ganapati. Antony and Bawri’s official line was that they needed a greater space than their small bungalow in Ipoh would allow. But those who knew the couple were well aware of Anthony’s difficulties with games of chance. They had moved from Ipoh to begin afresh. They imposed themselves upon Bawri’s mother, Laksmi, to live down a small lane lined with banana trees, fruiting papaya and towering coconut. It was practically romantic, if somewhat isolated. More sky-reaching coconut trees loomed over the squat single storey house. Banana leaves, waved their large, plush, green skirts in Far Eastern dances to the frequent warm breezes. An old, peeling, metal two-seater swing sat stately on the porch, its white paint revealing darker green beneath. Rust from its ironwork threatened to taint lighter clothes but, perhaps, no more so than the red/brown laterite of the garden. There was garden enough to plant a few bushes of bougainvillea, pink, white and orange bracts which were fading to purplish pink. That night, white, nightly scented, jasmine would perfume the equatorial air around the romantically inclined swing, while swift, fiery, miasmas of fireflies would dance sweet promises under tender moonlit skies. Anthony and Bawri’s was not an ideal marriage. Though a love marriage, there were disappointments. He was a Methodist and she Hindu. They both had fought discrimination in their increasing small town of Ipoh. A strongly willed Bawri, staunchly resisted the pressure for her to convert to his Christianity, ‘if my religion was good enough for my dear departed father, it is good enough for me’ she had pointedly reminded her husband. ‘Wasn’t he Marxist’ Anthony defended, ‘He was born Hindu, and that is good enough for me!’ barked Bawri, closing the conversation to his observations. Anthony had reached for the ever-present bottle of Glenfiddich, scrutinising the measure marks scratched along its side as he poured a generous measure of his favourite Scotch into a cheap glass, and sighed. Anthony’s Toyota exited the small dirt road and entered the compound. The gates swung electronically shut. Though tired, Mark experienced a more than pleasant surprise seeing a slim female waiting in the doorway. Bawri, five foot something, slim, lusciously ebony haired, was wrapped in a remarkably azure sari. It seemed to catch the essence of the morning light as she stood. Flashes of her exposed midriff intensified Mark’s curiosity as he gazed, almost in awe, at the vision she presented to his tired eyes. It was as if some efficacious Asian ointment had been splashed in his face, for he felt as if he was seeing the world for the very first time, a clear, beautiful, world containing the splendidly sculptured form of an Indian goddess, albeit a goddess who was, in actuality, the wife of his friend. Bawri wore a garland of fragrant, white, auspicious jasmine in her hair. It was tied in a careful knot at the back of her gracious head. Mark uttered ‘I.., I’m so grateful for you and your wife for putting me up like this. This place is amazing’. ‘Don’t mention it’ replied Anthony,’ we’re more than happy to have you, Bawri has been waiting anxiously to meet you, but you must be tired after your flight’. Mark was shy to take Bawri’s hand when proffered. It felt cool, strong yet soft and with just the polite amount of pressure. She looked him steadily in the eyes as she said ‘Welcome, I have been so longing to meet you. Anthony has told me all about you’. In that look Mark imagined days of mellow sunshine, nights gazing at tender moons and an eternity of soft comforts. That was enough for him to want to look away, embarrassed at his own thoughts. For the rest of the morning Mark slept in a room with a large, antique, wooden ceiling fan whirring the warming air around the room. The walls were painted in a light blue wash and the furniture, though not antique, was a heavy, solid teak wood. The floor was a herringbone parquetry, strewn with small black and white droppings from the naked ceiling gecko, locally known as ‘cik cak’. A groggy Mark awoke around one. He found his way to the shower space next door. It contained a small concrete and tile water container built into the wall to the right, and a shower with a large aluminium shower head, which deluged him with icy cool water. It was just what he needed to awaken from his fitful sleep. Refreshed and dressed, Mark made his way along the long inner hallway looking for his hosts. He found Bawri’s aged mother, Laksmi, wearing a plain loose cotton blouse and a faded, brown, Indonesian batik sarong. She was bent over, cooking on a charcoal stove balanced on pillars of loose bricks, outside the main kitchen. Through charcoal sparks they exchanged pleasantries the best they could with her broken English, and his lack of Tamil. Mark learned that everyone, bar the two of them, were out. He was encouraged to dine alone. Laksmi had freshly prepared a dish of Sri Lankan goat curry, and rice. Mark sat in the equatorial leaf-shadowed kitchen. Curry of the goat was, for him, a new idea. Mark could hear the elderly Laksmi outside, attending her chores - swishing dead leaves and checking pots for mosquito larvae. There was a meditative nature to her rhythmic movements and, after lunch, Mark sat on the veranda swing letting the gentle motion ease him to calm. It was evening before Bawri arrived back. Anthony had been invited to Kuala Lumpur to attend a vital interview, taking the Toyota with him to drive the five hours. Bawri worked part-time as a legal secretary. She filed for an Indian barrister, tidied his cluttered office and generally tried to help him find papers amidst his mess. It was a job that was all. Slowly, habitually, she walked the half mile or so from the small town, picking up provisions from the Indian stores along the way; bananas, small white aubergines, potatoes. Mark, still on the swing, heard a noise from the house. ‘I’ve always dreamed of being in London’. Bawri adjusted the glass louvers of the living room just enough so that Mark could see her face from inside. She gently bit her bottom lip, continued, ‘browsing the bookshops, taking walks by the Thames, it must be lovely there.' ‘Yes,’ said Mark a little startled ‘about once a month I take the train and visit the second hand bookshops, or the remaindered book shops’ ‘Remaindered, I’m not sure…’ ‘Books that have been sent back to the warehouse and sold off to the public’ ‘Oh, and you can buy those..’ ‘Cheap, yes.’ ‘Do you go to the theatre, I would love the theatre, Oscar Wilde or see The Mousetrap.’ 'I’ve been a few times, watching plays and shows’ ‘Shows, what shows’ said Bawri, unable to control her excitement. ‘I saw Bombay Dreams’ ‘That’s A.R.Rahman isn’t it’ ‘Yes, I like his music’ ‘Me too, En Swasa Kaatre is so romantic.’ then ‘Do you watch Bollywood films or Tamil films’ ‘I’ve seen some of both on TV, but it’s the music I like. I buy Rahman CDs in East Ham, London.’ ‘Really, but you’re a Mat Salleh, sorry a white man, an Englishman, and you like Indian music?’ ‘It’s a long story.’ ‘And one I’d love to hear too. Sorry, but I can hear mother calling’. It was a brief interlude and, for Mark, somewhat surprising. Bawri was quiet over dinner. She was seated where Mark had sat earlier in the day, but kept her head down as if chastised for her behaviour. Laksmi sat next to Bawri, also quiet, a chaperone. They finished the goat curry from the morning. Laksmi had freshly cooked some local long grained white rice, and a couple of small vegetable dishes with fresh santan (coconut milk). After dinner they all went their separate ways. Mark didn’t see Bawri again until the following evening. Anthony, apparently, was still away in Kuala Lumpur. Mark spent the day getting to know the area. His first port of call was the local stores, just along the lane from the bungalow and across the main road. The stores were housed in what appeared to be wooden lean-tos, their rusting corrugated iron roofs overshadowed by a large peepal tree. Opposite those buildings sat a small Hindu (Ganapati) shrine. It was a little faded and weather worn, but there were garlands of jasmine flowers freshly placed over the statue’s head, with marks of white ash, yellow turmeric paste and a smear of vermillion on its forehead, just above the beginning of the elephant trunk. Mark had read that Ganapati was the Lord of Obstacles, or was he the remover of obstacles, Mark couldn’t quite remember which. Mark followed a small path that evidently led to a partially covered market. It was late in the morning by the time he got there. Small brown children, who had played together around the market discards, ran off when they saw Mark coming. In the evening, after an early dinner of ‘String Hoppers’ (steamed noodles), Dahl and the soup-like yellow Sodhi (coconut milk coloured with turmeric root and flavoured with curry leaves), Bawri suggested an evening walk. She wanted to take Mark along to the gardens known as the Sungai Petani Bird Park (because of the number of caged eagles, owls and other birds seen there in the evening). Laksmi walked by Bawri’s side, Mark behind. They all entered the park and, for a moment, Mark was quite startled to see a peacock fan his feathers so rapidly, close to him. He stepped back. Bawri giggled at him, he smiled back. Laksmi frowned, sensing trouble. The evening was still, warm and as humid as the day. Mark’s thoughts were racing. He thought that he could see Bawri’s dilated black pupils in the brownness of her eyes. But he could have been wrong. It was night after all. But then there were her raised eyebrows as she smiled, the motion of her hand across her face, the way she brushed her hair away while looking at him, unflinchingly she had twirled a strand of captive hair around her finger, as her nostrils flared, just enough. ‘Wow, so many cages’ Mark had to break the spell. "In Tamil we call them Paṟavai kūṇṭu, in English bird cages. Many Chinese bring their magpies in the mornings, but here they also bring them along in the evenings too.” informed Bawri.’In the mornings the birds sing their little captive hearts out’. ‘Cries for help I shouldn’t wonder” chipped in Mark. Bawri laughed a short, clipped laugh.’The cages are so beautiful in this light, I wish I’d brought along my camera’ ‘Some things should be left to the moment Mark. Not captured like these birds’. She smiled again. Laksmi managed to insinuate herself between Bawri and Mark, as they looked at the birdcages. She kept her eyes on Bawri as they talked, and sauntered into the bird park. Laksmi said something to Bawri in Tamil. To Mark it sounded a bit harsh, but he didn’t know the language. Bawri shook her head, then looked away. ‘She is asking me when Anthony will be home. I said that I don’t know. He hasn’t rang yet. He is away too often, it’s lonely here.’ mentioned Bawri, then he looked at Mark, again with smiling eyes but, perhaps also with a hint of sadness in them. Mark thought he saw moisture at the corner of her eye, but it may have been the poor light. His attention was on the birdcages. Each has a perfect little black and white bird inside. Each appears to be the same size, same colours, yet each bamboo cage is unique. Some are stained a blood red, others black, or varying shades of wood colour, some engraved, others plain. ‘They can cost over eight hundred ringgit you know. The cages. Each cage can be over eight hundred ringgit. The men are hobbyists. Skilled craftsmen build their cages for them. The birds are well looked after. Tonight is the magpie specialists, tomorrow who knows, the Bee-eaters, perhaps.’ Explains Bawri.‘But still imprisoned’ They walk around the bird park with Laksmi chaperoning. In the centre of the park is a pond. ‘They are incredible’ says Mark pointing to half submerged, carefully sculptured, lotus leaves, the light and shadows playing across them. ‘You must see them during the day, when the lotus flowers are open, especially the pink, they are heavenly.’ Just then Laksmi spoke quickly, and a little sharply, again in Tamil, to Bawri,. ‘I’m sorry, but Amma thinks we should be returning home.’ ‘And what do you think?’ ‘I think that we should stay until the sun rises. We could watch from that bench over there, as the sun’s rays blow away the darkness.’ She said smiling and pointing ‘but I guess Amma does not approve. You are the first white man she has met, and does not entirely trust you.’ ‘In what way, doesn’t she trust me.’ ‘With me.’ They both laugh, causing Laksmi to tug Bawri’s sari once more, in reproach. They are quiet on the walk back to the bungalow, each with their own thoughts. On arrival they go their separate ways. Bawri to her bedroom, Laksmi to the bathroom nearest the kitchen, Mark to the room he had been given. After ablutions in the bathroom nearest his bedroom, and grateful for a cold water shower, Mark suddenly remembers that he has left his Flaubert novel in the front room. As the household is quiet, he assumes all to be asleep, or preparing for sleep. He dashes quickly into the front room draped only in his damp towel. Bawri is there. She is looking out at the night garden, watching fireflies, and is caught by moonlight streaming through glass louvers. She is in profile, beautiful, majestic. Bawri feels, rather than sees, Mark enter. Quickly she puts a finger to her lips and moves towards him. He enters the room towards her. Silently she touches the hairs on his chest, flickers a crooked, cheeky smile. Her eyes, caught in a sudden shaft of moonlight, are as if sparkling. Mark’s heart pounds uncontrollably. He stands still. She touches his shoulder, stretches herself up and kisses him on his lower cheek. He adjusts his pose, bends to meet her. They kiss, a full, long, kiss in the shadows. She puts her hand on the flimsy towel he is wearing, strokes him, feels him hardening. There is a sudden crack of equatorial thunder, quickly followed by illuminating lightning. The entwined couple jump just as Anthony’s car headlights brush away the room’s shadows. Bawri quickly untangles herself from Mark. She peeps through the louvers, to confirm her fears, then dashes to her bedroom to ready herself for her husband. Mark saunters back to his bedroom, turns just in time to see Laksmi disappearing into her room too. 'What had she seen’ thought Mark. Mark didn’t wake until quite late the following morning. When he did, he could hear Laksmi and Anthony animatedly talking, she with some urgency, Anthony puzzled, questioning. Mark heard the word Veḷināṭṭiṉar. It had been spoken before in his presence, so he guessed that it referred to him. 'Shit'. ~  Martin Bradley is the author of a collection of poetry - Remembering Whiteness and Other Poems (2012) Bougainvillaea Press; a charity travelogue - A Story of Colors of Cambodia, which he also designed (2012) EverDay and Educare; a collection of his writings for various magazines called Buffalo and Breadfruit (2012) Monsoon Books; an art book for the Philippine artist Toro, called Uniquely Toro (2013), which he also designed, also has written a history of pharmacy for Malaysia, The Journey and Beyond (2014). Martin wrote a book about Modern Chinese Art with notable Chinese artist Luo Qi, from the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China, and has had his book about Bangladesh artist Farida Zaman For the Love of Country published in Dhaka in December 2019. He is the founder-editor of The Blue Lotus formerly Dusun an e-magazine dedicated to Asian art and writing, founded in 2011.

0 Comments