|

Rome You had a way with light; Made it long for you. Cigarette between lips, Hair kissing spine, gazing Out the window at the Twinkling city below, you — as reachable as the smoke. Little did I know then, I, Just like the empire — replaceable in the end. Crave Too-warm nights, sheets discarded. Endless horror movies, buried faces, Waking with a start & feeling for the Reassuring shape. Across-table gazes & how they swept us away. Laughter That bounced off the stars. The endless Comfortable hum of your presence. These are the things I never noticed.  Philip Elliott is Irish, 23 years old and Editor-in-Chief of Into the Void Magazine. His writing can be found in various journals, most recently Otoliths, GFT Press, Peeking Cat Poetry Magazine and Subprimal Poetry Art. He is currently working on his first novel and a chapbook of experimental poetry. Stalk him at philipelliottfiction.com.

1 Comment

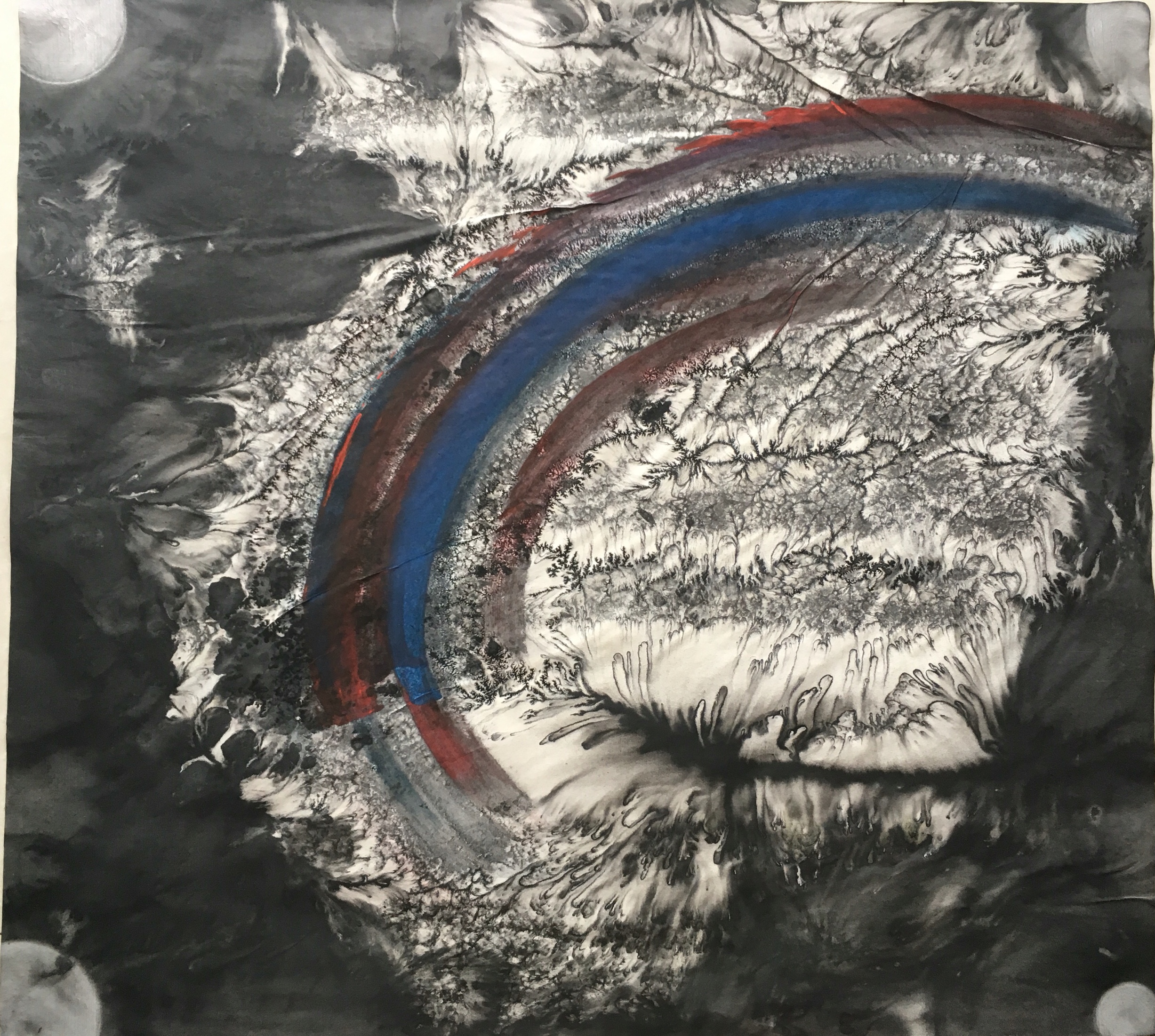

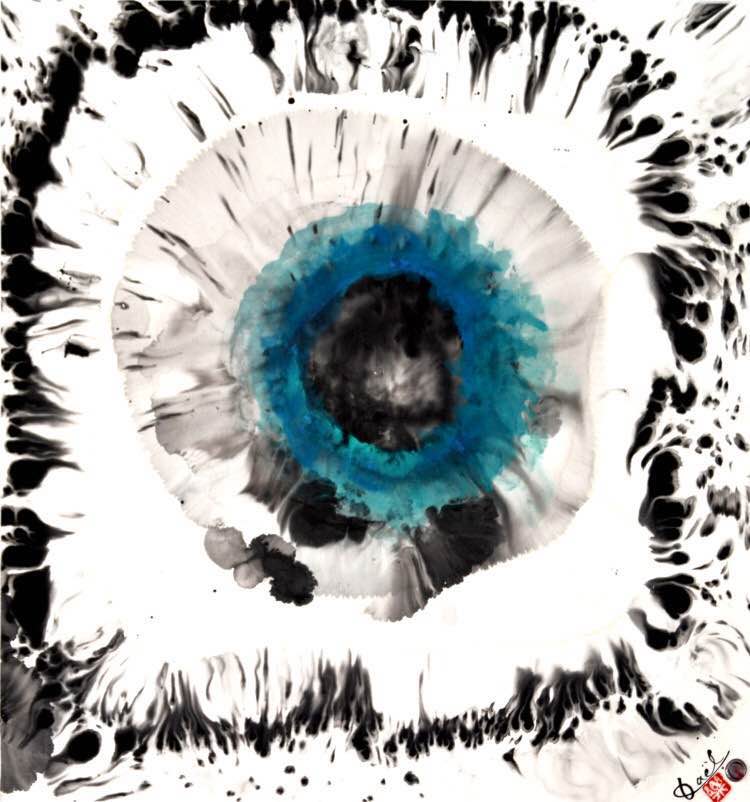

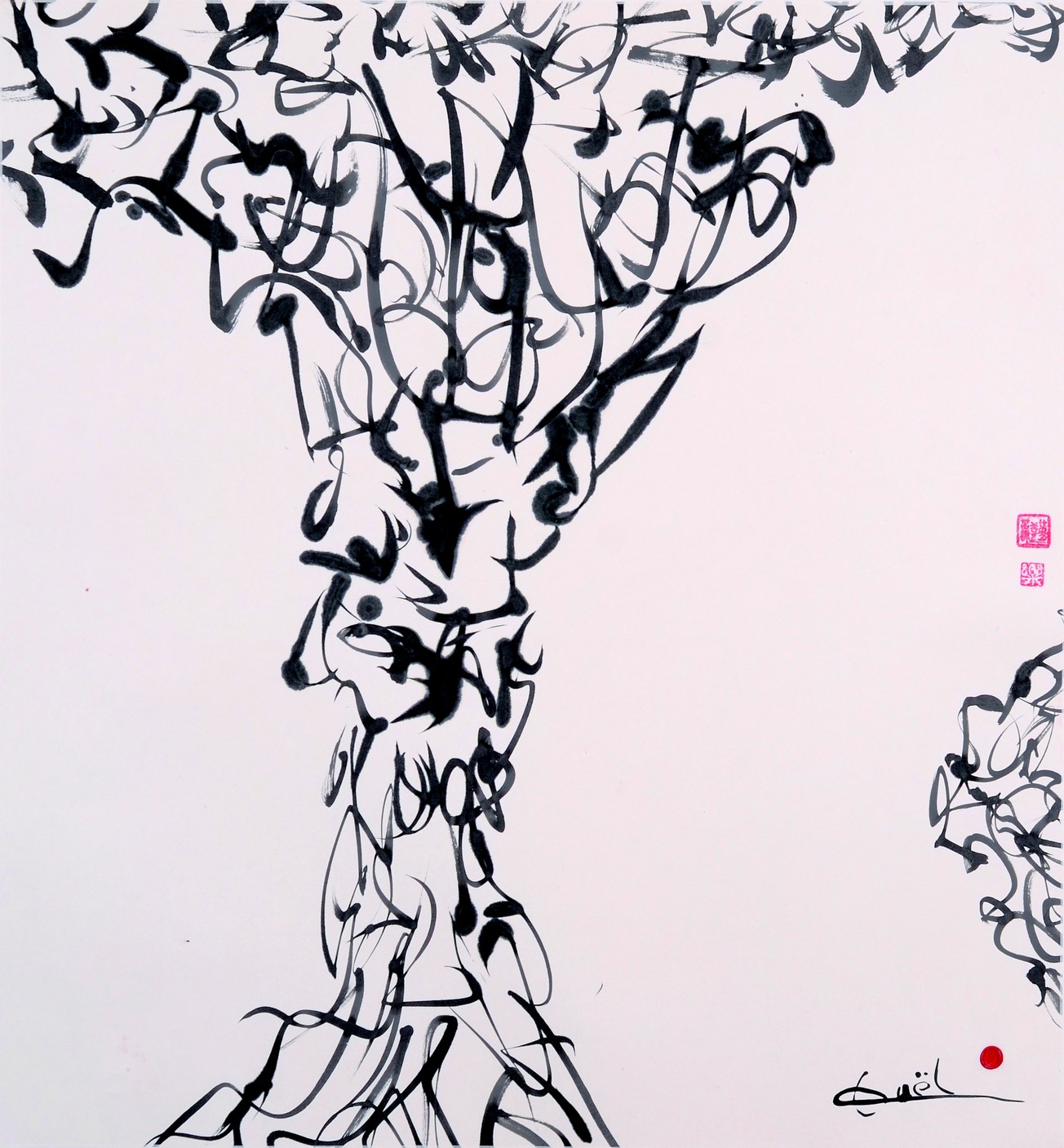

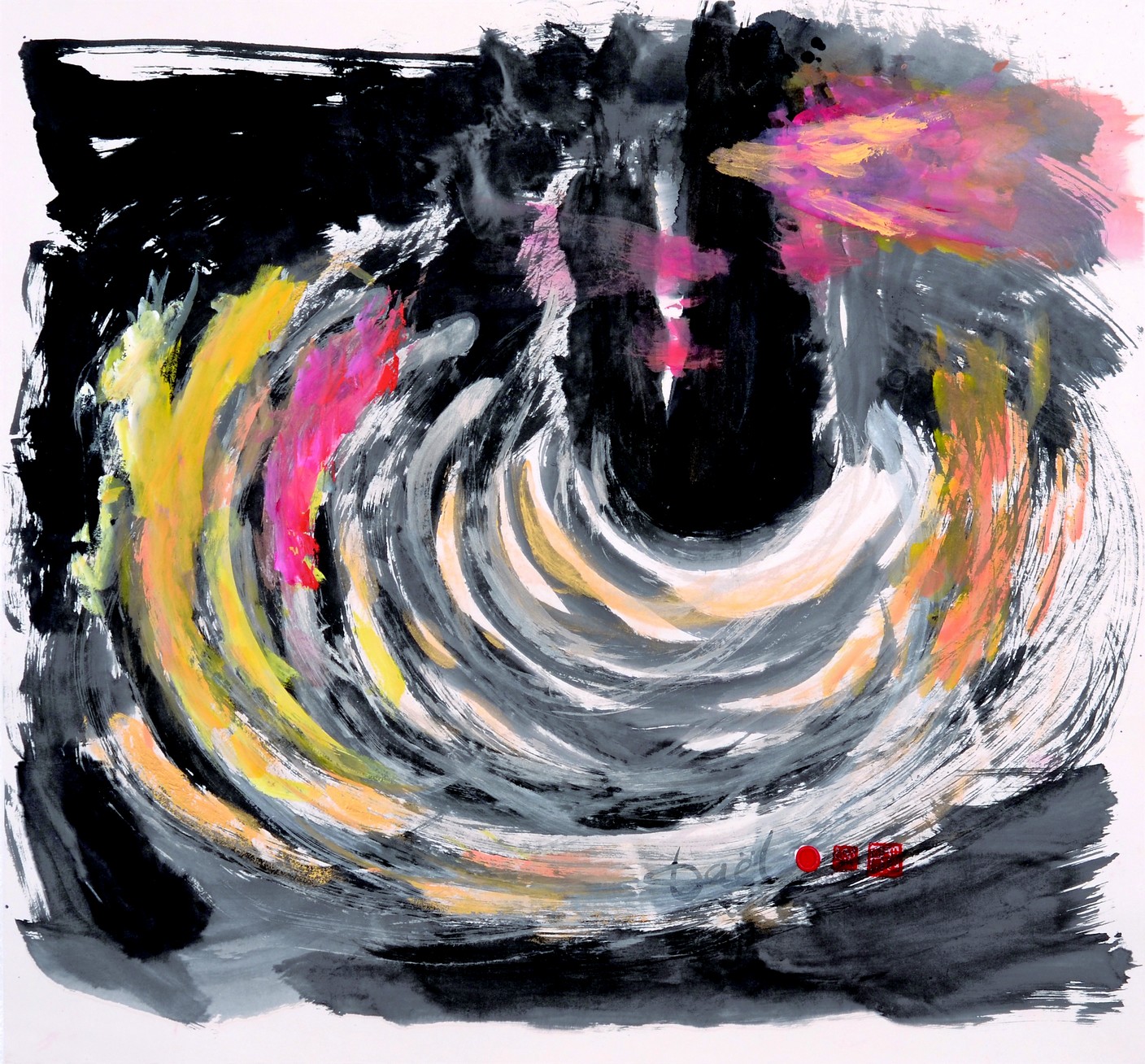

Gaël de Kerguenec (柯恺乐kē kǎilè) Painter, poet and linguist, has traveled and worked around the world for many years inspired by local cultures and languages enrich his art. Living in China for 10 years, he joined the Chinese techniques of ink painting and watercolor to its original and abstract art to push the Chinese traditional techniques to ongoing experimentation. Poet, he initially sought to recreate the feelings generated by his poems to move towards its present credo: " Painting ideas." The force crept into the brush stroke, diluting of inks and colors and how to distribute them on rice paper are specific to each work generating a constant renewal of sensations and feelings. His painting has gone through five periods: Purity, Complexity, Colors, Mists, Calligraphism. For more information, visit this website: http://www.gaeldekerguenec.com/kekaile/Style_Twenty_Three/en_text_677668.shtml Previous Chapters Letter 2 – Part 3 Gethsemane Greetings again, my dear. We have just concluded a visit from the oddest little fellow, a Mr Haven, of the Geographic Society, an undersecretary of some sort, coming to call on Robin. At first, it seemed he was come on behalf of the Society, but I am not certain that he was not more representative of his own designs. He arrived at our door at some half past ten; Robin had only just risen and taken his tea. Felix opened the door, for Mrs O and I were engaged in the kitchen. I discovered he had a caller when Felix was at my elbow proffering a card. I had Felix install the new arrival to the parlor whilst I went to the alley to alert Robin, who had taken out a chair and was reading. Robin’s reluctance was clear but in a moment we were seated with Mr Haven. What an odd-looking man. He wears an especially high collar and a long coat—I imagine in the hopes that it all gives him the illusion of height. In fact, the impression is just the contrary, as he seems to have fallen in to his apparel and may require some assistance in climbing out. Bushy brows, a pencil-thin nose, and full (nearly Negroid) lips show in the recess of his starched collar. He began by making certain that Robin was indeed master of the Benjamin Franklin—perhaps his makeshift clothes and worn-thin condition did not present the expected image of ship’s captain, of Arctic explorer. Once reassured, Mr Haven began asking Robin about the particulars of his adventure, and I thought, ‘How fortuitous; I have been wanting to gain such intelligences and now this strange little visitor can act as the instrument of their extraction.’ Or so I believed at first—however, it soon became clear that Robin was unwilling to divulge much to his inquisitor, especially in terms of specific details. He confirmed his essential route—through the Norwayan and Barents Seas—and his essential objects—the root cause of magnetism, etc., etc.—but beyond that already familiar terrain, Mr Haven’s own explorations were inconsequential. Robin deflected his interrogatories with consistently cryptic and vague responses. Eventually Mr Haven decided upon a new stratagem (Mrs O had brought us tea, and for a long moment the Society’s undersecretary held his cup and peered at the surface of his libation, as if answers to his queries may be found there). He said that a paper for the Society’s journal would be most valuable; then Mr Haven entered into such circumlocutions that I was not entirely certain at what he was aiming—that a book, presumably about Robin’s explorations (in addition to ?, in lieu of ? the aforementioned paper) may be even more valuable—however, such a book would not be published by the Geographic Society, but rather via a private firm, and Mr Haven seemed to be offering his services as agent . . . something to that effect. I noticed that as soon as Mr Haven embarked upon the topic of a book, Robin began to grow uneasy. I feared he was entering into a state akin to the one Mr Smythe’s traveler’s tale delivered him. The difficulty I experienced attempting to decipher the undersecretary’s design was exacerbated by my maintaining part of my attention on my brother, watching for signs of his slipping further along the unhealthful track. Robin kept hold of himself—though my perception was that it took some doing—and finally we were able to extricate ourselves from Mr Haven’s company; I expressed our appreciation for his visiting and assured him that Robin would consider all that he had intimated (I did not mention that chief among the goals of consideration was determining precisely what the odd fellow had proposed). I thought that perhaps Robin and I may begin such consideration as soon as our guest departed; instead, my brother returned to his seat and his book in the alley, though the day was turning grey and whispering the possibility of rain. (The following morning.) It is unlikely, anymore, to sleep so soundly through the night, but I did so. I believe my sleeping has been so poor for so long that utter exhaustion at last caught me up, and did me a good turn. As I was dressing I realized I knew not whether my brother was in his room or out on another ramble. When I stepped into the hall I listened at his door but heard nothing. Even if he had been muttering in tongues it would have been a relief (of sorts). Downstairs, Mrs O was already at work mixing the ingredients for biscuits. She had only got a pan of them in the oven when Felix, our early riser, appeared in the kitchen, his hair still needing a thorough wetting and combing; and he had a most perplexed countenance. I was cracking eggs in a bowl for Mrs O to scramble, with a pinch of salt and dried onion. I asked Felix what the matter was, and he asked us if we had taken any paper or a pencil. Upon waking he had gone directly to the table in the parlor where we had selected to store the art supplies; and he was convinced it had been depleted. Perhaps he had merely lost count, I proposed (though I know that would not be like our Felix, who has many of the business traits of his father). However, he was adamant that he had known the precise number when he retired. To his credit, Felix was not displaying childish pique but was nevertheless resolute on the matter. I assured him that I would reach the bottom of the subject, and he went about his morning ablutions. In a few minutes Agatha was downstairs, and Mrs O was setting out breakfast. Still, my curiosity about the paper and pencil clung tenaciously; and at my earliest opportunity I absconded upstairs: Mrs O and the children were thoroughly engaged in their respective tasks, and had no thought of my whereabouts. In the hall I at first went to my door, even masking from myself my true design. I stood with my hand upon the knob listening for sounds from Robin’s room; there was none. I thought perhaps, then, he had slipped from the house. I waited before his closed door for a full minute or more. I cautiously took hold of the knob, turned it, and stepped through an opening just wide enough. The room was dim so I hesitated a moment to allow my sight to compensate. Daylight lingered at the edges of the curtained window like a narrow frame about a picture, broken here and there. Robin’s dark shape became discernible on the bed. The impression was that he was dead asleep. My slippered feet disturbed the stillness of the room but little. I went directly to Maurice’s desk, still set in the corner of the room, and I recognized the odd shapes of the butcher’s paper, and the silhouette of a charcoal pencil, greatly reduced from use. There seemed to be images on the paper but the light was too poor to make them out. I looked back at Robin, who lay upon his side, his position unchanged; the form of the blankets hid his face. I quietly took up the paper, two irregular sheets; and stepped to the window. Holding the paper close to the wall and using the weakly narrow beams that crept into the gloom, I surveyed the images that Robin had drawn there. The first was a portrait of a handsome though haggard man. My first impression was that Robin’s unpracticed hand skewed the proportions and the subject’s eyes were too large; however, soon a second idea came to me: the eyes were not overlarge but rather they suggested the same haunted expression of Robin’s orbs. They were of course in charcoal grey but I surmised if Robin could have rendered them in full palette, the eyes would have been in the same glacial blue as his own, lending them a sheen of frigid isolation. The man in the portrait had an unkempt beard, again, not unlike Robin’s when he first arrived, and he wore a fur collar about his neck. The fur was here and there matted or missing in an odd patch. It was the portrait of a wretched fellow who had been through a hellscape of ice. I examined the other piece of paper to discover a more astonishing—and disturbing!—image: Also the portrait of a man, I suppose (it may be some manner of beast), but in three-quarter profile and nearly a full body’s rendering. The being’s hair was long and black and flowing, caught in the polar wind. It is glancing back, at the artist’s perspective; and even in partial profile, how to describe the look? It was a look of menace certainly—but yet so much more, too. It is astonishing that Robin’s inexpert hand could communicate so much regarding the being—perhaps a testament to the profundity of its impact on his mind, on his soul. The being’s gaunt, hairless cheeks, with darkened lips drawn in a sneer, provokes a sudden terror in the viewer, but then almost instantly perhaps after the initial shock has washed over, one senses that the terror is also felt by the being—as when a wild animal is cornered by hunters and it is both terrifying and terrified. That realization prompted me to refocus my attention to the being’s eye, and in its frozen, cadaverous attitude there was (unnoticed before) the echoes of pain and fear. And I knew these echoes were in Robin’s eyes as well. How could I, his only surviving family, not have seen them until now, reflected in the portrait of this polar being? I felt my cheeks dampen. I replaced the sketches to Maurice’s desk, and I blotted at my eyes with the sleeve of my blouse. I turned to look upon whom I had wronged and was startled to realize Robin was awake and looking at me; he had been silently observing as I snooped at his drawings. The profound sympathy I had felt only a moment before transformed into profound shame at my invasion of Robin’s privacy, and not simply the privacy of his room, rather the privacy of his past, of his memories, of his very soul. Perhaps my brother felt sympathy for me, too, in being caught so compromised. We peered at one another a long moment—then Agatha called for me from the foot of the stairs; I cast my eyes down and hurried from the room, which Robin’s and my muteness filled like a stifling gas. The images have stayed with me throughout the day, like images from a fretful dream that remain to oppress long after waking. (I was going to post this letter, my dear, but quite out of the blue Mr. Smythe has extended an invitation to Robin and me for tea at his rooms this very evening—‘on the occasion of becoming acquainted with new residents of Marchmont Street’ the invitation reads in Mr S’s crawling script. I must hold the letter until I may add report of this most unexpected development—it will perhaps afford an amusing closure to an otherwise troubling narration.)  Ted Morrissey is the author of four books of fiction as well as two books of scholarship. His works of fiction include the novels An Untimely Frost and Men of Winter, and the novella Weeping with an Ancient God, which was named a Best Book of 2015 by Chicago Book Review. His stories, essays and reviews have appeared in more than forty publications. He teaches in the MFA in Writing program at Lindenwood University. He lives near Springfield, Illinois, where he and his wife Melissa, an educator and children’s author, direct Twelve Winters I nearly caught a fish, Mum, I nearly won the race, I nearly beat the bully 'till he hit me in the face. I nearly passed exams and almost got the job but they gave the work to Sam - that overachieving nob! I nearly paid the loan off but then the car broke down so I nearly got a second job - but I couldn't get to town. We nearly went to Cornwall for a week beside the beach but the cost of renting caravans is far beyond our reach. I nearly gave up smoking but with all the stress at work I needed it to calm me down from dealing with those jerks... I nearly had it licked but I went along this week for another routine check up and the scan looked pretty bleak. It's ok though, I'm reconciled: I've been finalising plans. I'm going to have my headstone say "Here lies the Nearly Man! He lived an 'almost' kind of life - he never had his day, he spent his time just fishing for the one that got away."  Although born in New York, poet and musician Marc Woodward has spent most of his life in the rural English West Country. His work reflects those surroundings and often has a bleakness tempered by dark humour and musicality. Widely published, he has appeared in the Poetry Society and Guardian web pages, Ink Sweat & Tears, Prole, Page & Spine, Avis, The Broadsheet, The Clearing - and in anthologies from Forward, Sentinel and OWF presses. His chapbook 'A Fright Of Jays' is available from Maquette Press. A collection co-written with well known poet Andy Brown is due for publication in 2017. Previous Chapters Letter 2 – Part 2 Memphis (Later.) Just as I have been describing myself as some castaway, cut off like Crusoe from human fellowship, I find I must describe an incident much to the children’s benefits which is owed to Mr Smythe and Mrs O’Hair. When I was performing my toilet, the former brought to us a bundle of charcoal pencils, a dozen all lashed together with crimson string. They are the sort that artists use, and where Mr S acquired them I cannot imagine. Nevertheless he delivered them to Mrs O, who immediately recognized their potential value to the children. A few minutes thereafter the butcher’s fellow delivered the stew meat which Mrs O had ordered—and she pressed the fellow for any spare scraps of butcher’s paper he may have in his cart. He did indeed possess some odds and ends, cut at irregular angles, that he gave to her. So by the time I entered the kitchen both Felix and Agatha were at the table sketching pictures on the ragtag paper. They all could see that I was astonished—which amused the three of them exceedingly!—and forthwith Mrs O described the series of events that led to the surprising circumstance. For their having no formal training, I was pleased that the children’s ardor was nearly matched by their skills. Aggie was engaged in a mind’s-eye portrait of the calico cat (‘Patches,’ the children have dubbed her) who comes round the alley hunting mice and kindly laid saucers of milk. It seemed to me that Aggie had rendered the feline’s legs too short but had captured the shape and angle of her ears just so. Felix, meanwhile, was at work on a scene which did not at first come to me, two fellows and a young woman; but the ironbarred window in the background shed light upon the trio. They must be Macheath, Lockit, and Polly Peachum (from the Beggar’s Opera). What a funny young man, our Felix, to be so taken by such a work. Why not knights and dragons? Or something of a biblical bent . . . Samson in chains, Daniel among the lions? Or tri-headed Cerberus? Or even Prometheus bound to his boulder? I of course complimented the artists on their masterpieces, for I was truly impressed. Shortly I heard the front door, and it was Robin returning from his night’s haunting. I went to the hall to speak with him—though about what precisely, I know not—however, he and I stood stopped, facing one another for several moments, saying nothing. He looked the fellow who’d spent a long night. Dark semicircles drooped beneath his eyes, underscoring the paleness of the surrounding skin—and in the midst of these pools of pure exhaustion floated the ice-encased eyes of frozen blue. Robin was somewhat stooped, as if too tired to stand fully erect. He and I exchanged not a syllable, but I’m not certain if it was a silence of perfect understanding or one of complete incomprehension. Could it be both? I smelt no liquor on him, nor tobacco, nor any other scents which would lead one to conclude he’d spent an evening of carousing and debauchery—yet Robin’s exhaustion was beyond doubt. After another moment he initiated his trudging ascent, and then disappeared into his room. We did not hear from him for the remainder of the day. Watching his weary body move from one step to the next with such deliberate effort, it came to me that I have not inquired of Robin’s success (or failure) in his mission to reach the northern pole. His condition upon his arrival here—and his defeated and beaten demeanor since—would lead one to infer abject failure. Additionally, if he’d succeeded, would not Robin be hailed the conquering hero? Would there not be dignitaries of the maritime and geographic societies queuing up at our door? Would not the bells of London peal the momentous event? Yet, still, how near did my brother come to the goal? What obstacles did he overcome along the journey (for there must have been many)? Which ones undid him and his hopes? But attempting and surviving so awesome of a feat—is that not cause enough for celebration? Is that not itself an awesome feat? Robin possessed so many worthy ambitions: To solve the mystery of magnetism; to chart a northern passage to the Orient; to discover new species of fauna adapted to the extreme cold and general hostility of the environment; and to tread where no man had before set foot. I recall with perfect clarity Robin’s outlining of them to us the evening before he set sail. He was positively aglow! Equal parts golden lamplight, aged brandy, and enthusiasm for the commencement of a voyage so long in planning and preparation. It is difficult to reconcile that fellow, in a private room of the Albatross Tavern in Hastings, with this one, so defeated and downtrodden. I must gain some intelligences regarding the expedition, and surely, hence, some of its successes. Yet I do not want Robin to feel the target of a hostile interrogation, as if hauled before the Maritime Board, designed to find fault and lay blame. . . . I must leave off for now, my dearest. Aggie is calling for me. (I return.) Though we are a fractured family in your absence, Philip, I do feel that you would approve of the domestic scene which we managed to effect this evening. Mrs O had prepared a savory parsnip stew, though it was on the thin side, and I was able to coax Robin into joining us. I do believe he slept soundly for the remainder of the daylight hours; thus when we sat down to our homely repast, he appeared much improved. I know it is unorthodox, but I have developed the habit of allowing Mrs O to sit with us at table. It seems so unnecessary to trouble to set up the folding table in the washroom, just to have Mrs O dine alone—I believe it was a different matter when you were home, and we had a cook as well as a paid girl: the pair of them taking meals together did not make the washroom dining seem so sterile and austere. Then Mrs Walcott gave notice, as did Molly shortly thereafter—and we were left in an awkward circumstance. Fortunately, as you know, Mrs O’Hair was found in short order, on the good knowledge of Mr Smythe. At first, I had Mrs O continue the practice of taking her meals alone, but after a time it seemed a bit silly—and, besides, I missed having an adult with whom to converse at luncheon or dinner; in truth, I have found Mrs O a surprisingly able conversationalist, for an Irishwoman. Tales from her childhood and descriptions of her people’s strange ways have brightened many a dark hour. (Don’t fear, my dear, if you prefer to return to the practice of Mrs O’s dining in the washroom, that will be quite understandable.) To rejoin my main object: the little domestic scene. The table felt pleasantly full with the children on one side, Mrs O on the other, and Robin and I filling the head and foot. We were all quiet for a time, feeling somewhat unnatural at first, and occupied with passing the biscuit plate and the jam jar and such. As we were all just settled (and I was thinking what to say—imagine, I, lost for words), it was Robin, ironically, who initiated conversation, inquiring, ‘Are these the artists?’ meaning of course Felix and Aggie. He must have seen their sketches on the table in the foyer. ‘I am most impressed,’ Robin said. You can imagine how the children beamed. ‘They must have had a tutor,’ he said to me, taking up his spoon. ‘No, none—only what I have been able to teach them. You will recall my interest in art, when we were children.’ He appeared somewhat baffled by my remark; I wondered then if he recalled our childhoods at all. ‘We had a man on the Franklin, our second steerman, who was a talented artist, had studied for a time in Berlin, but circumstances drove him to sea.’ ‘You had some natural talent,’ I reminded him, ‘when we were children.’ ‘Did I?’ ‘Yes, indeed. In fact I remember a sketch of Max, our shepherd, that you rendered quite skillfully, given the age of your hand. I suppose you do not recall Maximus; he slept at the foot of your bed for years.’ My brother chewed his food thoughtfully. ‘I recall Max, certainly, but I am not certain of the sketch. I shall accept your word for it, dear sister.’ He returned his attention to the children, inquiring of their interests and their ages (he had lost track during his years at sea). The children, as you may imagine, gobbled down the attention with more gusto than Mrs O’s brothy stew. Robin’s animation was heartening; yet I wondered at his line: Did he question the children so thoroughly to diminish my opportunity to question him? Perhaps I was reading too much into his attitude. In any event, it was a nicely homely scene, and overall a balm of tranquility. I had good reason to hope for my brother’s full recovery. The only small blight was Felix’s fascination with Robin’s missing fingers, which were conspicuous in their absence since he ate with a spoon in his remaining digits. There was no mistaking the object of Felix’s attention as Robin would bring each spoonful of stew to his mouth. I was mildly anxious that Felix may make an inquiry as to the loss of them; but he did not. Surely Robin took note of Felix’s fixed gaze; however, he volunteered nothing. Perhaps he felt the topic to be uncouth for the dinnertable. Earlier, Mrs O had shown Aggie how to bake slices of bread softened with a few drops of cream and sprinkled with cinnamon and sugar—she called them ‘faerie scones’; and when we were finished with our stew, Aggie proudly retrieved the tray of treats, where they remained warm atop the stove, and brought them to table. We filled our cups with fresh tea, and Robin, as guest of honor, was prevailed upon to sample the inaugural scone. We watched expectantly as he took a bite—and instantly aimed a look of approval at the anxious Agatha: ‘Most excellent,’ he declared, chewing and savoring. As you may imagine, the neophyte cook nearly expired of joy. Look at the time! I must extinguish the candle, my dear, and retire. There is little more to relate of our evening. After dinner, Robin went to his room and was not heard from thereafter. My suspicion is that he availed himself of one of the many volumes in the chamber and read by lamplight. Oh, that you were here to warm our bed, dear husband!  Ted Morrissey is the author of four books of fiction as well as two books of scholarship. His works of fiction include the novels An Untimely Frost and Men of Winter, and the novella Weeping with an Ancient God, which was named a Best Book of 2015 by Chicago Book Review. His stories, essays and reviews have appeared in more than forty publications. He teaches in the MFA in Writing program at Lindenwood University. He lives near Springfield, Illinois, where he and his wife Melissa, an educator and children’s author, direct Twelve Winters On a one way trip the traveller has no intention to come to the point where the journey started. Loving you is a one way trip and I have no ticket to fly back to the point where I did not love you or when I did not know you.  Bashir Sakhawarz is an award-winning poet and novelist. In 1978 his first poetry collection was awarded first prize for New Poetry by the Afghan Writers' Association. Sakhawarz has published seven books in Persian and English. His latest novel Maargir The Snake Charmer was entered for the Man Asian Literary Prize by the publisher and was long-listed for India's 2013 Economist Crossword Book Award. His other works have been published in: Proceedings of the Ninth Conference of the European Society for Central Asia, Cambridge Scholars Publishing (Nov 2010), Images of Afghanistan, Oxford University Press (2010), Language for a New Century, WW Norton & Company; 1st edition (April 2008), English Pen, Asian Literary Review, Cha Literary Journal. In June 2015 he won the first prize for fiction from Geneva Writers Group. Bashir Sakhawarz is originally from Afghanistan and has lived in Europe, Asia, Africa and Central America. He has worked for a number of international organisations such as the United Nations, the European Union, the Asian Development Bank, the International Red Cross and various NGOs. Previous Chapters Letter 2 – Part 1 Jaffa Dear Philip, No doubt due to my brother’s sudden return to our lives, I find myself more and more borne back to the days of childhood, to a time before my father’s passing. One would think it a halcyon period, especially in comparison to the period after Papa’s death—but the utter chaos of that time seems largely expunged from my memory. I was a girl; then Father became ill with pneumonia after being caught in the terrible storm returning from Hampstead; then there was his funeral (nothing remains but impressions of blackness); then there is the period which is all but disappeared—when we were uprooted, like weeds from the garden, and relocated to become Uncle’s dependents, phantasmal years, banked in fog. It is the years before all of that which have been returning to me so vividly. The years when Robin was at my heel more often than not, like a devoted terrier, ready to engage in whatever game was my wish of the moment. We would fashion a corner of the arcade into a cottage of my own, the parameters established via well-positioned chairs and a blanket hung from the hooks normally used for baskets of flowers and herbs; there, I would play at being mistress, and my solitary guest for tea would be Robin—for tea, for cribbage, for the cutting of paper ornaments . . . for whatever suited me. My minion, two years my junior, was game for whatever amusement I chose. One day, it was late autumn and the weather was near to giving up its ghost to winter. A cold slashing wind made us abandon my ‘cottage’; it upended a chair and blew from the table where I held court the playing cards I was using to tell our fortunes. Unpracticed gypsy that I was, I had no foretelling of this being our final such party. He would turn to more boyish pursuits, often more solitary pursuits—which held no room for his elder sister. Such would be my pattern on that icy autumn day, as rain blew inward the soaked blanket which was supposed to shield us from cold calamity; I would not recognize a loss upon its earliest introduction, but only in retrospection could I make out the figure of Finality, the figure of Parting, as if he stood by, obscured in a grey gloom. Robin was loathe to return indoors. He seemed to be enthralled by the whipping wind and frigid pricks of rain. Could the seed have been sown that day? The kernel which grew into his obsession with the northern pole? I can only, now, wonder. I took him by the arm to urge him from the porch, and his skin was as cold as the pump-handle in winter, and slick with water too. I had the oddest notion—why I should recall it all these years hence?—that my fingers may freeze to my brother’s ice-cold arm. The irony is that that day seemed, looking back, to mark a kind of separation between us. By the following spring, Robin had become more independent in his occupations, no longer content to be my devoted playmate. One of the telltale signs was that his name for me changed too. I had time in memoriam been ‘Magpie’ on his childish lips; sometime that winter I became merely ‘Margaret’—the name by which everyone called me. Robin and I had lost our avian kinship. He, meanwhile, began encouraging the use of his true Christian name. I was alone in my recalcitrance, clinging to the familiar name of his childhood. As I obviously do still. Listen to me! Waxing with these long-ago memories. Robin’s return has indeed broke loose a torrent of recollections, enbrined with all manner of conjured meanings and emotions; and it seems my only egress for them lies in inditement: I am compelled to pay them out across the page in a tangled line of script. Thank you for indulging me, my dear. (Later.) It is still a goodly amount of time before dawn. I feel wasteful of the candle, but there is no returning to sleep and I experience a nervousness which prevents me from ever resting quietly until sunrise. I woke in the night and was of a mind to look in on the children when I heard footsteps in the hall; I glanced toward my bedchamber door just as a light retreated beneath it. I imagined it was Robin. After a moment I rose and donned my robe; I didn’t bother with a light of my own. As I entered the hall I heard the front door shut. As soon as I reached the bottom step of the stair I detected the scent of a snuffed flame. The candle in its holder was on the foyer table, and Robin was not about. He must have needed the night air, I told myself at first, still thinking of him in the terms of a boy—but I instantly amended myself. Robin is a grown man, a seasoned sailor in fact. Pardon my coarseness, my dear, but I could imagine that Robin felt the need for something more than night air. He would not need to travel far afield. Our section of the city, like every other perhaps, is teeming with such . . . attractions. I find I cannot fault him, for loneliness is a hard master, inflicting his lashes most vigorously during the quietest moments. Yet there will also be a sting, sharp and sudden, amid the most frenetic commotion. There was an instance of loneliness’s surprising strike on the morning of Robin’s arrival. Mrs O and I were busy at boiling the currant berries—she had been instructing me how best to detect when the berries are just the proper texture, and the children were having an animated disagreement in regards to the constructions of the Great Pyramids (their history lesson on that morning)—when, rather like a spasm of electricity, I felt the kiss of loneliness’s lash upon my soul. Then, for a moment, it was as if I were under water, and all the sounds of the kitchen—the hissing water of the boiling pot, the stove-door’s whining hinge as Mrs O stirred the fire, the children’s pitching voices—they were all muted and far away. I could only clutch at the knots of my apron and wait for the despairing pang to wash over me and, then, recede. It wasn’t long after that Robin arrived. I hope, my darling, that you are not so plagued with loneliness, and that you have amiable companions at your lodging and among your business acquaintances. Perhaps you would assure me of their comforts when you write, so that I may be certain you are not besieged with such cares.  Ted Morrissey is the author of four books of fiction as well as two books of scholarship. His works of fiction include the novels An Untimely Frost and Men of Winter, and the novella Weeping with an Ancient God, which was named a Best Book of 2015 by Chicago Book Review. His stories, essays and reviews have appeared in more than forty publications. He teaches in the MFA in Writing program at Lindenwood University. He lives near Springfield, Illinois, where he and his wife Melissa, an educator and children’s author, direct Twelve Winters |

StrandsFiction~Poetry~Translations~Reviews~Interviews~Visual Arts Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed