|

Previous Chapters CHAPTER 15 Adrift No one got a First for the B.A. Honours Degree in English Literature that year. Which made it difficult to apply for a Scholarship. Ashvini was lucky. One of four daughters of a Senior Civil Service Administrator, who held liberal views, and wished to give his daughters the best opportunities, he made Ashvini a lovely offer. He had got his oldest daughter into an arranged marriage that had proved disastrous, and was anxious not to repeat that mistake. He spoke to Asvini: “Look Ashu, I’d like to see you happily married and settled in life. But I want you girls to have a choice. I’ve kept –thousand Rupees for you. You may have it for your dowry, or you may use it for education abroad. If you choose to get married, I’ll try and find someone suitable. On the other hand, if you do decide to go abroad, I’ll help you with admissions and all the rest of it.” Ashu did the Essay and Entrance Test for Cambridge, and was accepted into Girton College. Shueli was happy for her friend. She herself had enrolled for the Master’s Degree – rather apathetically. Tara also joined her, and Manisha too, for a while. But, as one of their fellow students said when asked what she was doing, “Oh, just killing time, till they get me married off!” Killing Time? But time is all we’ve got, Shueli thought. A dreadful depression would seize her whenever anyone used the phrase. Killing time was like smashing your last water container in the desert. But time did drag, as the lecturer droned on and on to huge classes. There was none of the thrill or intellectual stimulation of their Honours classes. Their lectures were such a bore that they had devised what they thought was a fool proof method to deal with the endless tedium. “Let’s bunk class” Mani would say. “Yes. Let’s.” Tara and Shueli would agree whole-heartedly. They would sit somewhere on the side, right at the back of the class. It was Mr. Khanna’s class today, and he was talking about Macbeth. First would come the interminably long roll- call, reeling off name after name. Now he called “Manisha Mathur; Shueli Philipose; Tara Chatterjee.” Each would shout “Present” in response. And then, ‘Khanna Sahib’ launched into boring details about Macbeth and Shakespeare, in a monotonous voice: “Now I will ask you to consider – what kind of woman is this Lady Macbeth? Now , ob – vi – ous – ly theear fore (his characteristic way of stretching out the phrase) Shakespeare was creating an archetypal figure.” Professor Khanna never once indicated that he noticed the figures quietly slipping out of his class, or that the class was rapidly diminishing in size. But one afternoon, just after the three had vanished to the Coffee House, he did react. Looking out from the horn-rimmed glasses perched on the end of his nose, he suddenly asked the class “By the way – where did the three fair witches disappear to?” There was an outburst of laughter and clapping from the class, who realised he wasn’t referring to the witches in Macbeth. “Now that’s what you call a Classical Allusion” said one of the bright sparks of the class later. When Shueli and friends turned up for class the next day, they were teased mercilessly, and the title “three fair witches” stuck for a long time. To try and live it down, they had to compensate by sitting through stupendously dull classes, which left them dazed and yawning, like some lizards thrown up on hot sands, who don’t really know why they are there. Could they really drag themselves through two years of this meaningless existence? Outside, the real world beckoned. Manisha was already with a leading Theatre Group in New Delhi. But when someone came to ask if Shueli could act in one of their plays, Ammy ruined it all by saying in a censorious way, “We don’t want our daughters to go here and there, acting with all sorts of people.” The young man who had come to ask, was really stung. ”What does your Mum mean by saying we’re ‘all sorts of people’? We’re the best group in town.” Shueli just hung her head miserably. If she spoke she might have exploded in anger. She was beginning to feel more and more caged in. In her Diary she wrote: ‘How can I be happy when no one understands me, and I’m not allowed the freedom to do any of the things I’d really like to do? What can I do, with a Mother, Father and Sister who just don’t care how I feel?’ Her Diary was her secret confidante, to whom she poured out her secret sorrows, doubts and fears. All those painful stirrings of her youthful consciousness, which the world seemed so indifferent to, even ready to crush. ****** She had always been acutely aware of the pain of the world in which she lived. Now, this awareness became raw, like a sore that that couldn’t be healed. When she was a child, and they used to travel for three days by train to get to Honavar, or Tiruvella, she had seen the poorest of the poor, the deprived and dispossessed, and worse, the children of the poor, beg and plead for the smallest scraps of food, of life. Some of them had been mutilated to make them more useful, to arouse pity in the eyes of those who looked at them. But, the ghastly sights just seemed to turn people’s hearts to stone. Didn’t anyone care about anyone else in this cruel, indifferent world? She discussed it a lot with Papa, but human poverty and misery seemed insoluble. She remembered how at the Tiruvella bus stand, from where they caught the bus to Alwaye for the long train journey to Delhi, there were always women with hopeless hunger in their eyes and small, naked children with huge swollen stomachs. “That’s Rickets,” said Ammy. “Rickets?” Shueli and Gaya were puzzled. “But why do they have such thin legs—like sticks? Are their tummies full of rice –or worms? Gaya and Shueli were not sure what to make of it all, - whether to laugh or cry. One of the little boys, stark naked, except for a string tied under his swollen stomach, his huge eyes rolling, kept beating his chest, shouting “Ammo, Amme, -Thaaye (Give!)” Now and then, he would forget his job, and smile a beatific smile at them. They grinned back, because his smile was so infectious. “Rickets?” Ammy answered their question, “It’s caused by hunger and malnutrition.” But to their frequent Why, why, why, there were no answers. Shueli and Gaya were very little girls then. In the trains, too, there were countless beggars, some mutilated, holding out emaciated hands for a bit of charity. As they grew older, and kept asking these questions, Papa told them “Charity is not enough. The word Charity comes from the Latin root Caritas, which means Love, so unless people give, or share, with love, there will always be poverty.” This was before Independence, but even after, there was still a great deal of poverty. In Kerala, things improved a lot. People did everything they could to see that their children got some education. Though primary school education had become free, University education had to be paid for. People were often desperate just to get a helping hand to pull themselves up. Here, Shueli and her friends were drifting indifferently and listlessly towards the M.A. degree. There, a family would sacrifice anything to get the child into a college or some kind of training. Very often, letters would come pleading for a little help to “get Joey into the Engineering College. He got 90% marks in the Intermediate. But he can’t get admission here. Please Pilookutty, do whatever you can for Joey.” Or, it was a letter from the South side Ammama, telling Ammy to speak to her husband to “use his influence” to help Sosakutty get into the Nursing College. Shueli got a painful jolt when, early one morning, she found a young lad, perhaps a year or two younger than herself, standing outside the verandah. He had a small bedding roll, a little tin trunk, painted a bright olive green, and a few things rolled up in a plastic bag. It was beginning to get cold in Delhi, but he had a mundoo and thin shirt on, the mundoo rolled up to his knees, Kerala-style. “I’ve come all the way from Kerala – just to get a little help. I’ve been travelling over three days – that too, sitting up most of the way, as the Third Class compartments are so crowded. Chechi, please ask your parents to give me a little help. God will surely bless you and all your family.” He had a fine, sensitive face, but was painfully thin. When Ammy came out, he repeated his request. He was no beggar, just a poor boy in harsh circumstances. Ammy told him to sit down,, and brought him hot coffee, and some of the idlis they’d just had for breakfast. “Ammachy, if you help me, I’ll remember your kindness all my life, with a heart full of blessing. Not only I – but my mother and sisters, - we’ll pray for you always. At home, things are so hard. Father died three months ago. The little land we had, from which we got a few coconuts, and some tapioca, that too we lost, because we had to pay off father’s debts. At least before, we could somehow survive by eating a little sardine curry with tapioca. But now, my mother and two sisters are just drinking kanji vellam (rice-water) at night, going to bed hungry. Achayan’s first cousin’s son told Mother that you all would surely help.” Shueli remembered how, as a child, she had seen people turning up at the Tiruvella house ,who had trudged for miles from some outlying village, whose right to hospitality was accepted, whether or not they were distantly related, even if they arrived late in the evening.. There would always be some extra rice in the pot on the wood-fire. And one could always stretch the kootans (accompaniments to the rice). Anyway, no one was ever sent away hungry by Graany or Graanpaa, a custom which prevailed in most homes, including the home in Honavar. Things were different now in the cities, of course, but, on the whole, you still held out a hand to someone in trouble, especially if he was from your village or part of the world, and spoke your language. Ammy asked the boy “Have you passed Matriculation at least? Can you speak a little English?" The boy did know a bit of English, though he was evidently not too comfortable with it, and couldn’t express any of his deeper feelings – especially the pain and fear of coming empty-handed to a strange and distant place. Shueli remembered how Papa had pleaded with his mother, so long ago, for the chance to gain a bit more education. And how, at Oxford, he had been helped by the almost anonymous English lady. Hadn’t she told Papa to “ just give it back to someone else”? Hadn’t Honavar Appachan lived by the idea of ‘casting your bread upon the waters’? “Yes, indeed, and give no thought to whether any of it will ever come back to you.” So much so, that Honavar Appacha had even brought his widowed sister’s son to live with them, and be educated by him, despite his own large brood. “Believe in Divine Providence” he always said. Which was why, perhaps, when Papa took out, for the first time, in Lahore, a small Life Insurance, he had got a bitter letter from his family, blaming him for “caring only for your wife and daughters, and not relying on Divine Providence.” Now, Ammy and Papa were discussing what should be done. “He seems an honest boy, with a genuine desire to work and help his family Poor boy. So far from home, and so thin – hope he doesn’t have T.B.” Ammy could never keep her imaginative, yet practical side from asserting itself!. So that night, the boy, Chacko, slept on a mattress in the little room adjoining the verandah. The cook, Shivaraman Nair, saw to it that he was fed well. The next day Papa spoke to several people he knew, about Chacko. “Look, - there’s this young man from Kerala, - he’s a matriculate – knows a bit of English. He’s in a desperate situation, - badly needs a job. Can you fix him up with something at the Centre, perhaps in your office?” It wasn’t very easy. No one seemed able, or interested enough, to do anything for Chacko. He had to go and meet one or two of the people Papa phoned. One of them was not in his office when the boy arrived. The peon outside, dressed in a grand uniform, with a red turban, said phlegmatically, “Sahib not in his seat. Coming afternoon. You can be waiting.” He waited outside the office all day, hungry and tired, but never met the man. He came home exhausted, humiliated, and scared that nothing was going to work out for him. What would he do? Where would he go to? He didn’t even have money for the return fare. However, after almost two weeks of tramping around the streets of Delhi, foot-sore and sad-hearted,, he was offered a job in a Printing Press. He didn’t know anything at all about printing, but was eager to learn. He was more than grateful for the small salary. “I’m ready to work day and night for Mr. Chawla. He gave me a chance, after all.” And as for Shueli’s family: “You saved me from drowning. Can a human being ever forget that?” With a little money borrowed from Ammy’s housekeeping money, he rented a room near the Press. He was more than happy. ”It has electricity and water. What more do I need?” He often came to see them., was always eager to help Ammy with some of her household chores, and within three or four months had returned all the borrowed money. One day he appeared with a large basket of fruit and vegetables for “Our house.” “I’m learning all the work now., and Mr. Chawla has put me in charge of that section. I’ve started sending money home.” A year or so later, Shueli took the call which came when her parents were out. “Chechi, tell Ammachy and Appachan that Chawla Sahib has decided to give me special training in Printing. It’s a technical course – for six months. After that, my pay will become double.” Chacko went on to become a technical expert in his field. At night, he studied Hindi and English. He would ask Shueli to “lend me a few story books, Chechi. Some simple, good stories in English that I can understand.” When Shueli gave him a copy of David Copperfield, he looked at it, saying “It seems to be a very high book, Chechi, like the ones that you read. But will I understand it?” Shueli told him he should use a dictionary, and she would help him, if he marked out the really difficult words and passages he couldn’t understand. After starting, he told her, “It’s a good story. This David had a hard life, like us poor boys in this country. And this Charles Dickens, how he feels for the poor, and how he makes us to laugh and to cry.” Chacko went on to higher positions, with more responsibility. He was able to get his sisters some education, and see that his mother had reasonable comfort in her old age. But for every Chacko, as for every David Copperfield, there were many who struggled hopelessly, who just couldn’t beat the vicious cycle of poverty and failure. Just the other day, Mrs. Shankar, who had rented her servant’s quarter to a boy from Kerala, who was trying to find a job “as a clerk, or anything” , had found him lying dead on the charpoy. “Imagine! What a shock for us! We had to inform his mother, who is a widow, with three younger children. And what a headache for Shankar. He had to make a statement for the Police! Shiva, Shiva! Never again will we keep anyone in our Quarter.” Boys- and girls too (who usually came as nursing or Lab assistants), sometimes committed suicide because they had failed in an exam, or hadn’t got a job, with the future looking hopeless, and no possibility of “saving the family.” So, thought Shueli, when this was what was happening all around one, did one have a right to drift, and just waste the precious years? Attending the M.A. classes did seem like drifting on a dead sea, making her feel a kind of hopelessness, as if she were drowning, with no one to rescue her. CHAPTER SIXTEEN Breaking Out Shueli, adrift on a Dead Sea, knew she either had to get married, or break away, somehow or the other, from all these restraints. Set sail by her own star.Maybe get into the Theatre, which was the passion of her life. Or get to that distant City of Dreaming Spires, where Jude the Obscure had so yearned to go. As far as Theatre was concerned, Papa dismissed it as a most impractical idea. “There’s absolutely no future for English language theatre in the India of tomorrow. Regional languages will come back into their own – as they should. The best plays will be in Hindi, Bengali, Kannada, Malayalam. Of course there will be translations, and troupes from abroad will bring their plays here, but plays in our own languages will be what the people want.” As for Oxford, unless you had a scholarship, or your parents could afford to send you, it was just as impossible. Meanwhile, Manisha had already begun to drop out of College. She was acting in some much-talked-of productions in New Delhi, and was getting drawn into a group of sophisticated theatre people. Shueli wished she could join in, but her parents just said, “Finish your education, and then you can see if you are still so keen on Drama.” Ammy even went a step further. “We don’t want you hanging around with that Bohemian crowd, and getting burnt…” Shueli burst in, angrily, “I’d rather be burnt - in that fire. I want to live, to do the things I care about.” “You can do all that later. As far as we can see, the best security for a girl lies in a happy marriage.” “Oh, what is ‘security’? Does it lie in having a husband, and home, and children?” “Yes,” replied Ammy. “I certainly think it does.” Shueli felt helpless, unable to share her deeper feelings with anyone. If only she could see Arif again, and pour out her innermost thoughts to him. Wasn’t that what ‘security’ actually was? The freedom to be yourself with someone, in a loving relationship. The freedom to live, to grow, in a life shared with someone who loved you as much as you loved him. Or was this just another impossible dream? Maybe very few people held such perfection within their grasp. Hadn’t her Grand-Aunt Chinnam looked at her with her soul pouring from her eyes, even though it was only from a faded photograph, and hadn’t she warned her not to settle for false security, but grasp life, even if only for an hour, a day, a month, hold the wind within her fist? Yes. Yes. She had to fulfil that burnt-out, never-realised dream of her dead grand-aunt. Shueli had a dim apprehension, which became clearer as she grew older, that the unfulfilled hopes and dreams of one generation, fell like thirsty seeds, into the next generation, possessing them, claiming fulfilment. Families, Shueli often thought, were like those huge shells you find on the sea shore. If you held them to your ear, and listened keenly, you could hear the music of Time, sometimes roaring, sometimes whispering, in them. Her grand-aunt’s voice was a steady music, saying “Claim your own life. Claim it!” But this music was always drowned by voices talking about security, family, money, and such things. Some of her own friends were breaking away. Did they, too, hear that music, those voices? One of her childhood friends, Jasbir, a Sikh girl, had been a special friend when she was ten or twelve, sharing her bookworm habits. They had rather lost touch over the years, as Jasbir had got into the neighbouring Indraprastha college, not Miranda House. Shueli had often been to Jasbir’s home, and knew what a sweet, gentle lady her mother was. Jasbir’s father, on the other hand, was a regular patriarch and tyrant. “My father can’t stand the thought of my being a free and independent person,” Jasbir confided in Shueli. In College, Jasbir had become a Communist, and was active in Politics. “You know, Shooey, my father and brothers say that I am spoiling the Izzat (Honour) of the family, and should mend my ways.” Jasbir was laughing, a laughter which shook her tall, huge frame. “I’m going to give them a shock! Catch me fitting into that kind of life. Nothing doing!” Which Shueli thought admirable, but so difficult if you were trapped by bonds of love and family. It was alright if you hated your father and mother, to make a bold stand against them. In a way, her close relationship with her family seemed to be crippling her. One afternoon, Jasbir arrived in Shueli’s home, hair uncombed, a wild look on her face. She appeared truly distraught. “Aunty Amaal, Shueli, I’m through. I’ve run away from home.” She began to sob, so Shueli went and placed an arm around her. “My father informed me last week that he had arranged a marriage for me. And guess what, the man he chose was a forty year old contractor, whose first wife had died. Can you see me married to some old contractor, who’s never even heard of Classical Music, or Literature? I was furious, and began to shout, and cry, and plead, all in turns. My mother rushed to me, and put her arms around me, saying “Beti, beti, we love you. We women have to obey. The family honour lies in our hands. It’ll be alright.” So I replied ‘I don’t care a hang about the family honour. Why should I marry some old, uneducated widower contractor, just to please you all?’ Father shouted ‘Take this insolent daughter of yours out, and lock her up in the barsaati till she cools down. I am the head of the family, and wont stand for any disobedience.’ Then I lost my head completely, Amaal Aunty, I screamed at him: ‘You’re not fit to call yourself my father. I hate you!’ “ Jasbir was sobbing now “And then – you won’t believe it – he picked up his walking stick and raised it to hit me. I screamed. My mother put her arms around me, and covered me with her body. The wretched stick fell across her shoulders. I jumped up, and seized the stick from his hand, and flung it across the room. You know I’m quite strong. And I’m taller than my father. I yelled at him ‘If you ever hit my mother again, I’ll kill you.’ My father’s face just crumpled up, and he seemed to be shaken by soundless sobbing. He tried to hold my mother up. She was trying to calm me down. They made me lie down in my room, and gave me some pill which made me go to sleep for hours. When I woke up, it was about 2.30 at night. Everyone else was asleep. I knew if I stayed there, there would be more scenes, and I’d lose my freedom for ever. As soon as there was a little light, I got up, packed one or two clothes, took a few bits of jewellery, and whatever money I had, with a little I found in my mother’s shopping bag (she’ll forgive me!), and crept down the stairs. I managed to get a scooter rickshaw, and came straight here. “Oh god0god!” said Ammy. “What on earth are you going to do now? Isn’t it better you go home, and get some relatives to talk to your father who could try to change his mind?” “No. no. Not at all, Aunty. All the relatives will be on his side. For all you know, he’ll have the police after me. My mother may wish to help me, but he’s always bullied her. She’s helpless, actually.” Shueli took Jasbir into her room, and made her lie down and rest. Jasbir whispered to Shueli some of the secrets she couldn’t reveal to Ammy. “Shueli, you know I’ve joined the Communist Party. I plan to take Law classes, and go on to become a practicing lawyer. You know Sharat Bose? Well, he’s in the Party with me, and well, - you know, -we’ve fallen in love with each other. We’ll be Comrades in every sense of the word.. I’ve decided. I’m just going to run away with him, and we’ll get married. Maybe go to Calcutta, where his mother lives. She’s also a Party Member, and from everything Sharat tells me, she’s a wonderful person, one to respect and admire. I’m sick and tired of my father, and even my brothers, showing their muscle power to me, just because I’m a girl. After all, I drink as much milk as they do, and eat as many rotis. I’ll show them!” Shueli was quite floored by her friend’s tough physical resistance. “Maybe it’s because she’s a Sikh,” she thought. “They’re hardy people. Very physical and courageous, not too introverted, - maybe that’s why Jasbir is taking this very extreme step.” She knew she herself would never be able to fight her whole family in that way. “Maybe,” she said to Manisha, when she was telling her about Jasbir – “maybe – no, surely, - I would stand up for someone if we really loved each other, but the trouble is being so close to my family. That’s why I can’t fight them as Jasbir has done.” “Did her father have her followed?” Manisha asked. “Well, they did send someone across to ask if she’d come to our place. Ammy just replied vaguely, saying ‘Yes, I think she did drop in for a little while, but left soon after, and didn’t mention where she was going.’ Of course, they were too bothered about their Izzat, to ask any detailed questions. That would have given away how unhappy Jasbir is, and how they are bullying her.” Jasbir did manage to escape with Sharat Das, and wrote saying how happy she was. She had cut off all contact with her family, though she managed to smuggle in a bit of news of herself to her sad mother. A few years later, Shueli ran into Jasbir in Connaught Place, and the two friends hugged, overjoyed at meeting again. “Are you happy, Jasbir? How’s Sharat?” Jasbir looked slightly embarrassed. “I couldn’t write and tell you. I’ve been so busy with my Law Exams.. Sharat? Well, Shueli, - I left him. He really wasn’t much of a man. I got fed up with him and his mother. We had to live in a poky two-roomed flat. I think they expected me to do all the house-work. I said Nothing doing! So things began to turn ugly. He always took his mother’s side, and to add to it, he didn’t have a penny to make life a bit easier for any of us. No thanks! I got out of there, fast!” Jasbir was soon a thriving lawyer, who specialized in cases of injustice to women, and later, Shueli heard she had remarried. Manisha, too, was breaking free of the monotony of the M.A. classes, and getting more and more involved with the larger world outside. She got a job with a group who had started a Theatre Magazine, and was thoroughly enjoying it. As she was acting in several important theatre productions herself, she was much in demand. When she met Shueli on one of her infrequent visits to the College, she mentioned Mark Silgardo, who was a good bit older than herself, and a married man. “He’s such a remarkable man, not just handsome, - of course, he is divinely handsome, - no, it’s more than that. He is just about one of the most powerful actors, and he directs plays. What a range he has. He did Sartre’s No Exit a month ago, and now he’s doing the lead in Shaw’s Arms and the Man. Oh, Shueli – “ here, Manisha clasped her hands over her head, a look of utter rapture on her fine featured face. “Hey, Mani,” Shueli interrupted. “What’s happening? Are you falling in love or something?” “I am! I am!” Manisha twirled around the room, like a ballerina dancing a pas de deux. “I’m madly in love. Perhaps I should feel guilty about his being married. But all I can think of is that it’s me he loves. It’s not my fault. We were made for each other. She’s all wrong for him.” “But he’s married. And what will your parents say?” Mani’s face changed a bit, becoming slightly more subdued. “He has kind of tried to tell me how hopeless his marriage is. He even said that if it weren’t for his two kids – whom he loves – he would just leave her. He looked at me very sadly the other day and said, ‘I’ll work it out somehow, Mani. Just trust me.’ And as for my parents – of course I haven’t dared mention it to them yet. Both of them would just die. As it is, they’re very upset about my leaving College, and going into this Theatre business. Oh, they’re very old-fashioned and have the usual conservative ideas, - that I should settle down with some safe, dull boy from our caste and community. Not me Not me.” She grinned her infectious, lively grin, and was off like a meteor for her next rehearsal. All her friends were falling off, like leaves from a tree, Shueli thought. Only she and Tara remained. She wondered sadly which direction her life would take, and whether she too could achieve the freedom some of her friends had. She didn’t seem to have the courage to withstand her family, or just step out of the tight family circle. She rather admired her friends’ superb indifference to family and tradition. Mark Silgardo was a Catholic from Goa, while Manisha’s family were a highly respected old Hindu family. How on earth was it going to work? Would Mark eventually be able to divorce his wife, and leave his children. And surely it would make Manisha unhappy too? Shueli felt that breaking away from the tight bonds of her own family was almost an impossibility. And there was no knight in shining armour waiting to carry her off, either!  Anna Sujatha Mathai grew up in St. Stephen's College Delhi, where her father was Head of the English Department. It was an idyllic childhood, reading wonderful books, hearing poetry, seeing plays. She and her sister spent many sunny days exploring The Ridge, unimaginable now! Sujatha started writing Short Stories and Essays for The TREASURE CHEST, an All-India Children's Magazine edited by an American Editor, and translated into many Indian languages. At 14 she was chosen by Treasure Chest to be their youngest Special Correspondent! What she loved most was the Theatre. She was selected, at age 14, by the Shakespeare Society of St. Stephen's College, to be Viola in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night. Later, doing her B.A.{Honours} in English Literature at Miranda College, she won the College Drama Prize, and later, the Best Actress Award of the University of Delhi. Getting married at age 20, to a young surgeon, changed her life completely. In Edinburgh, she joined the University for a Post Graduate Course in Social Studies. She worked in that field for several years, in York, Sheffield, London. Leaving it all behind, coming back to small-town India, was traumatic for her. She used to write on scraps of paper, and throw them away. Her sister, in Bangalore, sent her a cutting in which American professor, Howard McCord of the Univ. of Seattle asked for poems by "avant-garde young Indian poets" for his Anthology. Her sister wrote "At the most, you'll lose a few stamps!" Prof McCord's warm response to her poems, made her start taking her writing more seriously! Her first poems were published in P. Lal's MODERN INDIAN POETRY IN ENGLISH. She continued to write, and, later, moving to Bangalore her dream of theatre was somewhat realised. She had roles in plays by Shaeffer, Ibsen, Sartre, Pinter, Tennessee Williams, Lorca and others. She was a co-founder,with friend Snehalata Reddy, of THE ABHINAYA POETRY/THEATRE GROUP. Her poems have been published in The Commonwealth Journal; Indian Literature; The Little Magazine; The Times of India; Dialogue India; Chelsea (New York); The London Magazine; The Poetry Review (London), Two Plus Two (Switzerland.), Contemporary Asian Poetry Ed. Agnes Lam, Hong Kong/Singapore: Post-Independence Poetry in English ed. by Arundhathi Subramaniam She was among 4 poets "show-cased" on the 50th Anniversary of the Sahitya Akademi. She was an Associate Editor of the prestigious Literary Journal, Two Plus Two,based in Lausanne, Switzerland. She has 5 collections of Poetry in English, and her poems have been translated into several Indian and European languages. She now lives in Delhi.

0 Comments

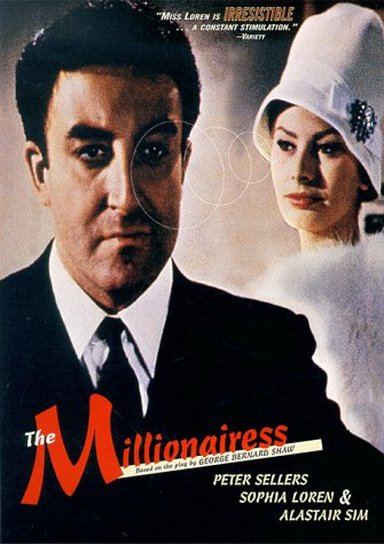

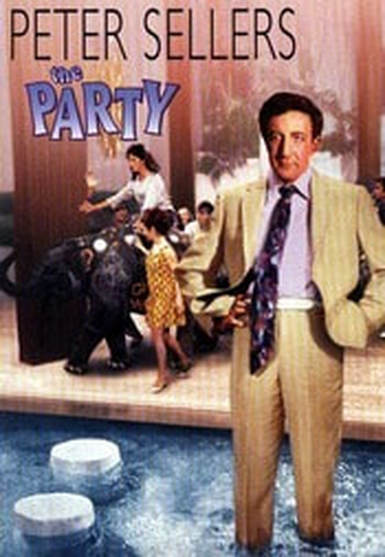

Film Review Hanif Kurieshi Here's an odd thing. As a mixed-race kid growing up in the south London suburbs in the 1960s, I liked any film starring Peter Sellers, particularly I'm All Right Jack, Dr Strangelove and The Pink Panther. But my two favourites were The Millionairess and The Party, both of which starred Peter Sellers as, respectively, an Indian doctor and a failing Indian actor. In both films Sellers, in brownface, performs a comic Indian accent along with a good deal of Indian head-waggling, exotic hand gesturing and babyish nonsense talk. He likes to mutter, for instance, "Birdy num-num," a phrase I still enjoy replicating while putting on my shoes. And I'm even fond of singing Goodness, Gracious Me, the promotional song from The Millionairess, produced by the peerless George Martin. So, at the end of the 1960s, my sister, mother and I came to adore Seller's Indian character, repeating his lines aloud as we went about our business in the house, because we liked to think he resembled Dad. My father, an Indian Muslim who had come to Britain at the end of the 1940s to study law, was, in his accent and choice of words, upper-middle-class Indian. As a child and young man he'd spoken mostly English since his father - who liked the British but hated colonialism - was a Colonel and doctor in the British Army. However, we didn't think of dad's accent as Indian: for us it was a mangling of English. There was a standard, southern, London accent, and he didn't have one. He was a mimic man, but a bad one, as all colonial subjects would have to be. If the white Englishman was the benchmark of humanity, almost everyone else would necessarily be a failed approximation. Dad could never get it right. Indians were, therefore, inevitably comic. And because my father, as a father, was powerful and paternal, our teasing shrank him a little. Dad was also sweet, funny and gentle, but not wildly dissimilar - in some moods - to the hapless character Sellers plays. My sister and I had been born in Britain after all. We knew how things went and Dad didn't. As I wrote in The Buddha of Suburbia, "He stumbled around the area as if he'd just got off the boat." If my father's way of misunderstanding hadn't been comic it might have become moving or even upsetting. When I got older, my younger self embarrassed me. I vowed not to look at those movies again. Foolishly, I'd allowed myself to be tricked into loving a grotesque construct, a racist reduction of my father and fellow countryman to a cretinous caricature, and I'd be advised to backtrack on my choices. Yet recently, re-watching the films, when I stopped weeping, my views changed once more, and I want to think about what I liked in them. My mother had married a coloured man in London in the early 1950s, at a time when one fear in the West was of unauthorized boundary crossing, or miscegenation. It was with miscegenation that the terror of racial difference was placed. Men of colour could not and should not be desired by white women, nor should they breed with them. People of whatever colour could only go with others of similar colour; otherwise some idea of purity would be defiled. Racial separation thus ensured the world remained uniform and stable. That way the most important thing - white wealth, privilege and power - would be sustained. Nor was the crime of 'crossing' trivial. We should not forget that Hollywood's Production Code banned miscegenation from the American cinema for thirty years. As children of a mixed-race background, though not particularly dark-skinned [I'd describe myself as 'brownish'] as children we were subject to some curiosity. People were worried for us because, surely, being neither one thing nor the other, we'd never have an ethnic home. We mongrels would linger forever in some kind of racial limbo. It would be a long time before we could enjoy being different. It is with this in mind that we should look at The Millionairess, while not forgetting that Sidney Webb, a close friend of Bernard Shaw - the author of The Millionairess - and a supporter of eugenics, warned that England was threatened by 'race deterioration.' I was surprised to read that Shaw himself wrote, "The only fundamental and possible socialism is the socialisation of the selective breeding of man." Despite this, we should consider how few mixed relationships were shown on screen. Anthony Asquith's movie, made in 1958, was adapted by Wolf Mankowitz from Shaw's 1936 play in which the male lead is Egyptian. In Asquith's version, a divine Sophia Loren - an aristocratic, rich Italian called Epifania Parerga - falls in love, while attempting suicide, with an Indian Muslim doctor who, at first, sees her as nothing but a nuisance. I must have seen this on television, and I don't recall many people of colour appearing in the movies I saw at the cinema with my father, except for Zulu and Lawrence of Arabia. This was also a time when black filmmakers were virtually invisible. Not only is Dr. Ahmed el Kabir a Muslim man of colour and voluntarily poor, he is cultured, educated and dedicated to helping the indigent and racially marginalised. Most natives in most movies, of course, had always been shown as thieves, servants or whores, or as effeminate Asiatics. We were always considered dodgy. Roger Scruton writes in England: An Elegy, "The empire was acquired by roving adventurers and merchants who, trading with natives whom they could not or would not trust..." We were thrilled, then, that the movie would include no covert fantasy of coloured men raping white women, a trope which seemed to me to be almost compulsory since A Passage to India and The Raj Quartet. And The Millionairess does, in fact, have a nice Hollywood ending, with the mixed-race couple together enjoying one another. While the Millionairess looks creaky and silly in places, but is saved by the performances of the leading couple, The Party is a lovely film. Sellers, obviously a great comic actor, is at the peak of his mad inventiveness, and Blake Edwards is a brilliant director of physical comedy. Composed of a series of perfectly judged vignettes - a carousel of increasingly bizarre incidents -the movie becomes riotously anarchic as Sellers' innocent Indian creates, inadvertently, total chaos at the house of film producer General Clutterbuck, to whose party he is mistakenly invited after blowing up his movie set. At the beginning of the movie, Seller's character Hrundi is shown playing the sitar, reminding us that at this time - it is the year when Sgt Pepper was being played in every shop, party and house you visited - Indians were supposed to possess innate wisdom, beyond the new materialism of this dawning vulgar age in the West. When, soon after, Hrundi attends the smart Hollywood party, it isn't difficult to identify with his apprehension. Don't we all feel, when going to a party, that we are about to lose our shoe in a water feature and will spend the next hour on one leg? Yet he is even more out of place than even we would be, and unnerving in his strange, formal politeness. "Do you speak Hindustani?" he asks strangers, who are baffled by his question. "Could you ever understand me?" would be a translation. "Do you want to?" The Party was released in 1968 and I'm surprised at my enthusiasm for it at the time, since this was also the year of Enoch Powell's grand guignol 'Rivers of Blood' speech. If my father and other Asian incomers seemed wounded in Britain, vulnerable, liable to abuse, looked down on, patronized, tolerant of insults, racism made me want to be tougher than my father. My generation would rather resemble the black panthers than the pink panther. We knew we didn't have to cringe and take it, for this was the era of Eldridge Cleaver, Stokely Carmichael and Angela Davis. These blacks were so sexy with their guns and open shirts and attitude, and I'd been mesmerised by the black-gloved salute of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico Olympics. There's nothing macho about Hrundi. He's a different sort of heterosexual leading man to those usually preferred in the American cinema. When, at the party, he meets one of his heroes - a tough but charming cowboy with an iron handshake and a movie reputation for shooting red Indians - Hrundi is offensively absurd in his sycophancy. Yet there is something to his softness. The other men in the film, those involved in the film industry, are shown to be somewhat brutal if not summary with women, whom they patronize and infantilize. Hrundi is different. Perhaps women and people of colour occupy a similar position in the psyche of the overmen, which is why his friendship with a coy French girl [Claudine Longet] who sings like Juliet Greco, is so touching. The woman and the Indian, both subject to the description of the other, the brown man coming from 'the dark continent' and the woman as 'the dark continent', can recognise one another as supposedly inferior. Both are assumed to be inherently childish. As it happens, there's more to Hrundi's idiocy than pure idiocy. He seems like someone who could never be integrated anywhere. And his gentle foolishness and naiveté becomes a powerful weapon. If you've been humiliated and excluded you could become a black panther or, later, join Isis, taking revenge on everyone who has suppressed and humiliated you. Or you could give up on the idea of retaliation altogether. You could perplex the paradigm with your indecipherability and live in the gaps. After all, who are you really? Not even you can know. When it comes to colonialism, the man of colour is always pretending for the white man: pretending not to hate him and pretending not to want to kill him. In a way, Sellers' baffling brownface is perfect. And in some sense, we are all pretending - if only that we are men or women. Eventually Sellers' useful imp escapes the power and leads a rebellion. Or, rather an invasion in the home of the white master, involving an elephant, a small army of young neighbours and the whole of the frivolous Sixties. The swimming pool fills with foamy bubbles into which people disappear, until no one knows who is who. In a carnivalistic chaos they all swim in the same water. At the end of the movie, he and the French girl leave in his absurd little car. In both films, the Sellers' character knows he has to be saved by a woman. And he is. Significantly, it is a white woman. Walk out tonight into the city portrayed in The Millionairess and you will see the great energy of multi-racialism and mixing, an open, experimental London, with most living here having some loyalty to the idea that something unique, free and tolerant has been created, despite Thatcherism. Out of the two films, The Millionairess looks the least dated since its divides have returned. It has been said that Muslims were fools for adhering to an extreme irrational creed, when the mad and revolutionary creed, all along, was that of Sophia Loren's family: extreme, neo-liberal capitalism and wealth accumulation, creating the Dickensian division in which we still live. Equality does not exist here. This city's prosperity is more unevenly distributed than at any period in my life-time, and the poor are dispersed and disenfranched. Not only does our city burst with rich Italians and many millionaires patronizing urchins and the underprivileged, but a doctor committed to serving the financially excluded would be busy. London has reverted to a pre-1960s binary: a city of ghosts simultaneously alive and dead, of almost unnoticed refugees, asylum seekers, servants and those who need to be hidden, while many rightists have reverted to the idea that white cultural superiority is integral to European identity. Since those two films with their brownfaced hero, we have a new racism, located around religion. And today the stranger will still be a stranger, one who disturbs and worries. Those who have come for work or freedom can find themselves blamed for all manner of absurd ills. As under colonialism, they are still expected to adapt to the ruling values - now called 'British' - and they, as expected, will always fail. However, if the Peter Sellers' character begins by mimicking whiteness, he does, by the end of both films, find an excellent way of forging a bond with his rulers, and of outwitting them. If the West began to exoticise the East in a new way in the Sixties, the Sellers' character can benefit from this. For the one thing the women played by Sophia Loren and Claudine Longet lack and desire is a touch of the exotic and mysterious. It becomes Sellers' mission to provide this touch. For Akbir and Hrundi, the entry into love is the door into the ruling white world of status and privilege. To exist in the West the man of colour must become, as Fanon would put it, worthy of a white woman's love. A woman of colour has little social value, but a white woman is a prize who can become the man's ticket to ride. By way of her, being loved like a white man, he can slip into the west, where, alongside her, he will be regarded differently. Perhaps he will disappear; but maybe he will alter things, or even subvert them, a little, and their children will either be reviled or, out of anger, alter the world. A Hollywood ending tells us love must be our final destination. Yet there is more complexity to these lovely finalities than either film can quite see or acknowledge. Birdy num-num indeed. ~ Also published in Sight&Sound (BFI) October 2017 issue.  Hanif Kureishi was born in Kent and read philosophy at King’s College, London. In 1981 he won the George Devine Award for his plays Outskirts and Borderline and the following year became writer in residence at the Royal Court Theatre, London. His 1984 screenplay for the film My Beautiful Laundrette was nominated for an Oscar. He also wrote the screenplays of Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987) and London Kills Me (1991). His short story ‘My Son the Fanatic’ was adapted as a film in 1998. Kureishi’s screenplays for The Mother in 2003 and Venus (2006) were both directed by Roger Michell. A screenplay adapted from Kureishi's novel The Black Album was published in 2009. The Buddha of Suburbia (1990) won the Whitbread Prize for Best First Novel and was produced as a four-part drama for the BBC in 1993. His second novel was The Black Album (1995). The next, Intimacy (1998), was adapted as a film in 2001, winning the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film festival. Gabriel’s Gift was published in 2001, Something to Tell You in 2008, The Last Word in 2014 and The Nothing in 2017 His first collection of short stories, Love in a Blue Time, appeared in 1997, followed by Midnight All Day (1999) and The Body (2002). These all appear in his Collected Stories(2010), together with eight new stories. His collection of stories and essays Love + Hate was published by Faber & Faber in 2015. He has also written non-fiction, including the essay collections Dreaming and Scheming: Reflections on Writing and Politics (2002) and The Word and the Bomb (2005). The memoir My Ear at his Heart: Reading my Father appeared in 2004. Hanif Kureishi was awarded the C.B.E. for his services to literature, and the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts des Lettres in France. His works have been translated into 36 languages. |

StrandsFiction~Poetry~Translations~Reviews~Interviews~Visual Arts Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed