|

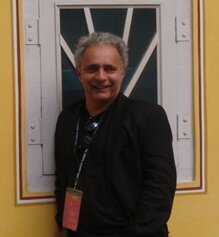

Essay ~ Hanif Kureishi Hanif Kurieshi on Writing His First Novel All first novels are letters to one's parents, telling them how it was for you, an account of things they didn't understand or didn't want to hear, saying what couldn't be said, providing them with a bigger picture. It was the late 80s, and I was in my early 30s, when I began to work on The Buddha of Suburbia. The two films I'd written previously, My Beautiful Laundrette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, had bought me time and money. The success of My Beautiful Laundrette had given me confidence that the writing tone I'd found could be extended into the novel I’d wanted to write as a teenager. I had been no good at school, but always felt more alive than the people around me. I was a horny bookworm, and novels got through to me. I thought I'd do one. I did several. They were not published. But I did write what became the first chapter of The Buddha of Suburbia, as a short story for the London Review of Books, published in 1987. I believed that was that. Then I kept thinking there was more material. I had an intense experience which can happen to writers, when you understand that your subject is right there; you have lived it already, and that world is waiting to be converted into scenes. If people were not writing books about people like me, I'd write one myself, spitting out all the painful things, rudely, lightly. Someone said to me, write your pleasure. I did. Reading the first paragraph of The Buddha now, I'm surprised to notice that the hero, Karim Amir, announces his nationality three times. I guess he was insecure. Like David Bowie, he was eager to find an identity, throw it away, and start again next day with another one, brand new. In 2015, Zadie Smith wrote a lovely introduction to my novel. She describes discovering the book at school, which she calls a first for us 'new-breeds'. She says, 'Irresponsibility is an essential element of comic writing'. And Karim Amir, my boy and avatar, who likes both boys and girls in bed, and where possible both at the same time, is determinedly wild and rash. But Karim knows something that most people don't. And what he knows is priceless: that being a person of colour isn't at all like being white. No white person walks into a room and finds it weird that there are only white people present; no white person thinks of themselves as a problem for others, a question, a perplexity. No one asks them where they're really from. Whites belong in the world. It's theirs, they own it, and they don't even appreciate it. But they do get defensive and cranky when you point it out, as you have to, repeatedly. Karim understands that being a person of colour means being bullied all the time. Yet while whites might consider themselves superior, it's more original and enjoyable being underneath, laughing up at the poverty of privilege. Karim begins to get that his disadvantage is his advantage. Then he stops caring either way. He's free. If anyone thanks me for writing The Buddha of Suburbia, or says it meant something to them, I am always grateful, since I'm reminded of how a few decent people, along with some good stories, once got me out of a bit of a jam, and into a more open world. As I think about my novel today, looking back on myself, I wish I were that boy again, free on his bike. But I know he's still in me, funny, hopeful, rarin' to go, always up for it, going somewhere. ~ (Also published in The Guardian as 'There were no books about people like me', on 25th April 2020)  Hanif Kureishi was born in Kent and read philosophy at King’s College, London. In 1981 he won the George Devine Award for his plays Outskirts and Borderline and the following year became writer in residence at the Royal Court Theatre, London. His 1984 screenplay for the film My Beautiful Laundrette was nominated for an Oscar. He also wrote the screenplays of Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987) and London Kills Me (1991). His short story ‘My Son the Fanatic’ was adapted as a film in 1998. Kureishi’s screenplays for The Mother in 2003 and Venus (2006) were both directed by Roger Michell. A screenplay adapted from Kureishi's novel The Black Album was published in 2009. The Buddha of Suburbia (1990) won the Whitbread Prize for Best First Novel and was produced as a four-part drama for the BBC in 1993. His second novel was The Black Album (1995). The next, Intimacy (1998), was adapted as a film in 2001, winning the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film festival. Gabriel’s Gift was published in 2001, Something to Tell You in 2008 , The Last Word in 2014 and The Nothing in 2017. His first collection of short stories, Love in a Blue Time, appeared in 1997, followed by Midnight All Day(1999) and The Body (2002). These all appear in his Collected Stories (2010), together with eight new stories. His collection of stories and essays Love + Hate (2015) and What Happened (2019) were published by Faber & Faber in 2015. He has also written non-fiction, including the essay collections Dreaming and Scheming: Reflections on Writing and Politics (2002) and The Word and the Bomb (2005). The memoir My Ear at his Heart: Reading my Father appeared in 2004. Hanif Kureishi was awarded the C.B.E. for his services to literature, and the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts des Lettres in France. His works have been translated into 36 languages. Author Photo Credit : Jose Varghese

0 Comments

Fabrice Poussin teaches French and English at Shorter University. Author of novels and poetry, his work has appeared in Kestrel, Symposium, The Chimes, and many other magazines. His photography has been published in The Front Porch Review, the San Pedro River Review as well as other publications. Poetry ~ Dr. Muralikrishnan T.R. The Drizzle that made me a poet How do I forget that day Which got treasured in a May The first clouds of dark monsoon Brought by the winds so soon The palms and mangroves gave Their nodding assent with a rave The children of my neighbourhood Sprinted back as quick as they could The dense gray merged with the azure The wild symphony of nature in full measure A violent silence did the earth embrace While the anxious birds flew back in haste The soothing wind gave a warning Of heavenly showers impending Then from the horizons far and wide Trumpets of rain sounded with pride The gentle drops kissed with kindness The yearning earth with infinite richness From the earth’s bounty sprung the redolence A primitive rumbustious uncanny observance As the celestial theatre unfolded the plot The protagonist arrived at the spot Bringing solace to every vacant soul, Unleashing uproar to humanity as a whole. ~ A Digital Replay I measure Time Not the way the clocks do And not the way the world perceives But in positions Where my mental framework Engulf magic moments and Irreparable losses. My flashy recollections Of over-protected childhood, Dim lit classrooms, The nauseating odorous toilets of the school, My sexual awakening, My first ill-fated romance, The lip to lip kiss with adolescence, The eyes that stole glances of ivory coloured damsels, Graduation to a money minded world, Salary and arrears, arranged marriage And its consummation Nagging worldly responsibilities, Bereft of mirth and emotion, The first gray hairs and their uneasy concealment The never ending construction of home… The text of life continues To create new forms and shapes And every mind with a colourful multimedia- facility would recreate its past the way I did Since I know mine may not be the first and the last. ~  Dr. Muralikrishnan T.R. is an Associate Professor in the Department of English in MES Asmabi College Kodungalloor with twenty five years of teaching service in various colleges. He teaches poetry in Undergraduate and Graduate Classes. He is a recipient of ELTRePs India award 2014-15 (ELT Research Partnership) granted by the British Council in 2014. He has already published a few poems in various edited volumes. Poetry ~ Alan McCormick Keeping Close from a Distance Escape from the viral airwaves, the incessant mantras, the deadly numbers, the scapegoating and washing of hands, the everyday fuzz of social media, being PA to your own dwindling life, the bills, the shopping list, the desperate search for protection, a cure no sanitizer nor edict can muster. The two-metre stare, the cross to the other side of the road, the masked bandits and retracted handshakes, the burbling inside, the turbulence of bedtime waking, the selfishness of survival, the crawling towards the light, pleading to be saved so you might live on. And yet your child sleeps, innocence in dreams wishing it all away, your love suddenly unlocked, your meaningless chatter held at bay, your fears now only for them, that you might save them, that the selflessness of survival might mean keeping apart, and you grab your moment of quiet and hold them tight. ~ What if (For Trump, Johnson, and all who sail with them) What if your killers clap you after they administer your lethal injection? What if your leaders build and sell the bombs that fall onto your town? What if they drink the rivers dry and fill the sky with lead and poison? What if they profit from death and share the spoils amongst themselves? What if they knew the plague was coming and took no decisive action? What if the people who were blamed and sacrificed rise up to take over? What if the love between them and for the world becomes the new way of life? Well, then there would be less need of leaders, and the earth might breathe again.  Alan McCormick lives with his family by the sea in Wicklow, Ireland. He’s been writer in residence at Kingston University’s Writing School and for the charity, InterAct Stroke Support. His fiction has won prizes and been widely published, including in Salt’s Best British Short Stories, Confingo, Lakeview, and online at Words for the Wild, Strands, Dead Drunk Dublin, 3:AM and Époque Press. His collection, Dogsbodies and Scumsters, was long-listed for the 2012 Edge Hill Prize. He also writes shorter pieces in response to pictures by artist, Jonny Voss. See more of this collaboration, along with Alan’s own fiction at www.alanmccormickwriting.wordpress.com Short Fiction ~ Jonathan Taylor 10.02 a.m. Here I am again, like usual, sitting behind the till, waiting for a customer to come in to the shop. Lahlahlahlahlah. 10.44 a.m. Here I am still, sitting behind the till, waiting. Tuesdays are slow days, and today is Tuesday. At least I’ve got some digestives under the counter. 10.47 a.m. Still here at the till. Mrs Parker says I should always be ready, even if there are big gaps. Mrs Parker’s the manager of Hurt Heads. She’s also my mum, but I’m not allowed to call her that in the shop. She says it’s the ultimate irony me working for Hurt Heads, after what happened. But she also says I don’t know what irony is so not to worry. The only thing I’m worried about now is that it’s cold in here. So I’m putting on my coat. Hidden in one of the pockets is a tea-cosy – well, it’s a hat, really, that belonged to someone else once. But it looks like a tea-cosy, all knitted and patterny. I keep it in case the someone else comes back into the shop. If mum found it, she’d go ape, yelling stuff about fair-weather friends and dangerous driving and prosecco. I don’t think that would be irony. 11.04 a.m. I’m humming a tune: Lahlahlahlahlah. I can’t remember what the tune is. Perhaps when mum gets back I’ll ask her – I mean, Mrs Parker. Mum says music is good for mindfulness. She’s got the Beginner’s Book of Mindfulness at home. She says that since the accident we all have to concentrate on the moment, not dwell on the past, or worry about the future. 11. 06 a.m. So here I am, concentrating on this moment: sitting-waiting-sitting-waiting-humming-waiting-not-eating-digestives. This moment’s a bit boring, to be honest. Hope it’ll be gone soon. 11.18 a.m. I’ll have a digestive at 11.30 if no-one’s around. I know that’s thinking about the future, but it’s only a few-minutes-away-future, so maybe it doesn’t count. 11.27 a.m. Three minutes till digestive-future. Lahlahlahlahlahlahlah. Oh, a customer is coming into the shop. Boo. It’s kind of like a train announcement: Unfortunately, we’re sorry to report that your digestive is delayed. We apologise for any inconvenience caused. 11.33 a.m. The customer, who’s wearing a tie with helicopters on it, is buying Greatest Hits of Black Lace and a small china dog which nods when you touch its head. I do all the things I’m meant to: I take Greatest Hits of Black Lace and small china dog off him, look at the price stickers, tap the numbers into the till, press MISC, then SUB-TOTAL. I have to hold SUB-TOTAL down for it to work. It’s an old till, as old as my mum, and not like the high-tech ones they have in Asda. While I’m holding SUB-TOTAL down, I like to imagine everything and everyone stops for a second – you know, like musical statues. Even the people outside the window freeze. Sometimes, when I’m on my own, I press it down to see what happens, if anything moves. It’s like the world is holding its breath in – concentrating on the moment, as mum says. As soon as I let go of SUB-TOTAL, I have to do lots of other stuff – counting change and offering a bag and saying thank you, and Mr Helicopter Tie says “Thank you” back and nods, over and over again, like a small china dog. 11.34 a.m. At last: digestive time. 1.35 p.m. I haven’t had any lunch, just six digestives, so I’m all tummy-and-headachy. Headaches make my thoughts get all jumbled. Mum says whenever I feel like this, I should focus on what I’m doing now, and the feeling’ll go away. But the problem is that I’m not doing anything now. Instead I’m remembering this thing from a few weeks or months ago, and the funny thing is that it feels in my head like it’s happening now: a lady is coming into the shop. She’s got what looks like a tea-cosy on her head, with knitted flowers on it. Tea-cosy lady is picking up a saucer – it’s one of those willow-pattern ones – and looking at the price underneath. She brings it over to the till. She’s staring at me and coughing. So I’m coughing too, cos it might make her feel more comfortable. Then suddenly she’s asking: Do you know who I am? I’m looking at her face under the tea-cosy, and as if by accident I’m saying to her: I don’t remember your name but I think you’re one of the fair-weather friends my mum talks about. You were driving the car and didn’t visit me in hospital. Tea-cosy lady’s eyes are all watery and trembly like bubbles. I’m wondering if you pricked them with a pin, would they burst. I haven’t got a pin so instead I ask her: Would you like to gift-aid the saucer? She shakes her head. Then she grabs my hand and it’s a bit too tight and she’s crying like someone has actually popped her eyes and saying lots of sorries without taking a breath. She takes out a bunch of chrysanthemums from one of her bags and holds them out to me, crying big tears all over them. They are beautiful and rainbowy and crinkly. The flowers, not the tears. Later, though, my mum comes back and asks who they’re from. And next morning, when tea-cosy lady is in the shop again, mum appears from nowhere. She’s shouting things at tea-cosy lady which don’t sound very mindful or irony-ish. She knocks tea-cosy lady’s tea-cosy off, and pushes her out of the door. Tea-cosy lady doesn’t say anything. She just looks at me with those bubbly eyes through the window, and runs off, leaving her tea-cosy behind. My mum forgets about it, and I pick it up and put it in my pocket when she’s out back. It’s my one and only secret. 2.04 p.m. No customers. Nothing to do. Lahlahlahlahlahlahlahlahlahlahlah. 2.44 p.m. I’ve run out of digestives. Boo. 3.56 p.m. I’ve been here for a year and a half now. I don’t mean I’ve been sitting behind this till for a year and a half – although it kind of feels like that. I mean: I’ve been working in Hurt Heads shop for that long. At least, I think it’s that long. It’s hard to remember when most days are the same. My mum says it’s good experience – gets you back out there. I’m not sure what I’m supposed to be experiencing out there, or here, well, apart from sitting and waiting for my mum, I mean Mrs Parker, to come back to cash up. Waiting for going-home-time. I know it’s bad of me, but the funny thing is I don’t want it to be going-home-time or sitting-in-the-shop-time either. Both are mum-I-mean-Mrs-Parker-times. I think, before the accident, I used to have some non-mum-times. I wish I could remember them now. I wonder if the tune that keeps going through my head – you know, the one that goes Lahlahlahlahlahlahlah – comes from those before-times. 3.59 p.m. I’m staring out of the window, and suddenly I’m looking at her: tea-cosy lady – well, tea-cosy-lady-without-the-tea-cosy. She’s near the shop window. I want her to look in. I want her to stop. I don’t care about fair-weather friends or prosecco or dangerous driving or irony. I want to hold her hand again and give her her tea-cosy back. Oh no, I think she’s walking past. I want her to stop. I am pressing the SUB-TOTAL button on the till. I am holding it down. ~  Jonathan Taylor is an author, editor, lecturer and critic. His books include the poetry collection Cassandra Complex (Shoestring, 2018), the novel Melissa (Salt, 2015), and the memoir Take Me Home (Granta, 2007). He directs the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Leicester. He lives in Leicestershire with his wife, the poet Maria Taylor, and their twin daughters, Miranda and Rosalind. His website is www.jonathanptaylor.co.uk. Poetry ~ Henry Bladon Clouds I peer through a slatted blind at the window of your world and see your pensive moments, locked in stasis clouds of smoke surround your thoughts. what fragmented wonders exist beyond the shores and fields and hills of artificial boundaries? There are no external troubles and nothing rattles in your mind you save no place in your design for frenzy or fast-paced living or needless worry your thoughts are of palm trees and dancing, of distant lovers in summer nights, for they are dreams created in clouds of smoke. ~ Echoes of Purgatory The echoes of purgatory as Paradise is lost in Hellenic majesty olive groves on Mount Olympus the green grass of ancient lands that cannot be seen from on high except in the mind’s eye searching for a sun-soaked lawn in lazy August where dying figures are given up to the worship of Helios. ~ The Good Old Days Remember the good old days, when we drove to the shops? Remember when we travelled the globe and cared little for trees? Remember smog and noise and starless skies which were replaced by pure streams and fresh breeze? Still think they were the Good Old Days? ~  Henry Bladon is a writer of short fiction and poetry based in Somerset in the UK. He has a PhD from the University of Birmingham. His latest work is the poetic novella 'Notes from the State of OMNESIA.' His work can also be seen in Poetica Review, Pure Slush, Truth Serum Press, and Flash Frontier, among other places. Short Fiction ~ Soufyaan Timol A battle is one stride, the first and the last. The next. Always the next. Asukai had seen the great masters of Nal-Har manipulate the grace of this stride like mummers manipulate puppets, had seen them exercise a command so absolute over their motion that even the slightest detail would not escape it. You could not hide such control. She knew almost instantly; the man standing twelve paces from her was no novice. Not even an expert. Beyond that. In how he moved, and how he did not move, she knew. The Linewalker tried to hide his mastery, to act green and brash but, the moment he entered a stance, she understood she was facing someone who had reached the top, and who dwelt there. A cool breeze swept over the open plain, through the naked blades of grass and up the hills a few miles west. Veins of crimson streaked through the cloud-laden sky, nightfall close. But for the two of them, not a man breathed for leagues around. Not a man to witness, not a man to contemplate the beauty of what was to come. Asukai doffed her cloak, let it fall with a gentle thud. The muscles in her back stretched when she reached for the daggers in her boots, which she discarded; they were bothersome during a duel. "What is your name, Linewalker?" she asked. "That I may know it before I take your life." He chuckled, but only softly. "Shichiro. I assume the Cutthroat is only a brand?" She flashed a grin, entering the Dark. "Asukai Kelsatra, from Nal-Har." Shichiro Ka. The name was famous enough, in taverns and among ruling outlaws. Not simply a Linewalker. One of the best swordsman of the nation. Asukai rolled her shoulder. We’ll put that reputation to the test. Last, when she had removed any piece of fabric that might slow her down, the woman unsheathed her longsword. The winds of early summer whispering against her bare arms, she brandished it towards the Linewalker. "You people do the job of bounty hunters these days?" He raised his own blade, an inch shorter than hers, with his left hand. "What you did is way beyond bounty hunters." Asukai took a step forward, a single one. This was where the battle began, where everything else ended. A mistake now, a slip or a lapse, was death. "I killed a few men. What? Fifteen, sixteen at most." He did not answer, but his pretty eyes said everything. Not how many you killed, who you killed. Calm as the silence before a storm, they circled each other, neither of them making a move to attack. A sudden wind blew from Shichiro’s direction. She caught a strong earthy scent, like fresh cut wood. It reminded her of the forest marshes after a dry season. His limbs pulsed with every step, on the very edge of attack, of a lethal strike. But no, her guard was up, and any half-good swordsman could recognize such a trap. Four seconds and Shichiro’s sword fell into his right hand. All conceit lost from his demeanor, all softness shredded from his gaze. Asukai sighed inwardly. Few were those who did not underestimate her, the same few who usually wound up being hard to fell. A sudden shiver ran down her back, a caged fear she had not known in years- They pounced at the same time, not a split-second between their charges. The blades collided in muted whistles and metallic clacks. Red and blue sparks soared. Death edged close, to be stopped by another manner of death. Just as easily, they broke apart, unscarred. The exchange had lasted less than a heartbeat. Shichiro's eyes met hers, rimmed with exhilaration. Chilled with vigilance. He was not surprised, not anymore. A battle is one stroke, one brush. May it last a few seconds, or an eternity, the dance is one unbroken movement. Where the earthen ground, dry with chill, had been a thirsty battleground instants earlier, it now lived single held breath. Quiet, more fearful than anticipating, like a plague-struck village awaiting its incineration. She treaded on the balls of her feet, her footfalls resounding like hollow drums. The Linewalker thrusted for her chest. A sidestep, block, strike, and they slipped past each other. Asukai did not blink at the sudden gust of dust-laden air. Have I met my match? They revolved around each other, drawing ring upon ring of choked anticipation. Is he the one to fell me? She had killed two hundred and sixty-eight men over the last two decades, half in open combat, and twelve in duels. Three had been Linewalker masters. Two different martial arts she had mastered, her body and mind become a sculpture of polished marble, where not a hair's breadth of imperfection was allowed to exist. And here... here was a Kenesiro light-haired who defied every notion of that reality. Asukai struck. Her blade found his side, slicing through hardened leather and coming just short of flesh. She retreated. Under the ebbing light of sundown, they danced. More than not, a spear's length of palpable tension stood between them, waiting to be crossed. Night fell easily, with time frozen in a sphere around them. Starlight glinted off his blade, the gleam matching that of his dark eyes. A shallow cut appeared on her left arm, another on her leg. Inconsequential; Linewalkers did not poison their blades. Unprompted, a part of her studied Shichiro Ka, beyond her active scrutiny of his form and movement. His skin the light tan of northerners of this country, eyes the shiny black of polished crystals, with a face made of hard lines and a body even harder, he looked younger than what his gaze told. A man of focus, she could tell, of patience and sober determination. There was yet a streak of defiance in his poise, something she could not exactly identify. As far as her own duty went, he did not look like a rapist. Then again, who does, really? He was a murderer, only a lawful one. She permitted herself the slightest smile at the thought. And attacked. Their swords met like abrupt lightning, thunder made physical and shaped into blades. Once, twice, left, right, a slash and a stab. He fended off her every strike, and her every one of his. The impacts vibrated through her weapon and up her arm. From nowhere, his fist slammed into her ribs. Nearly panicking, Asukai managed to withdraw, earning another cut down the length of her back. The woman raised her guard and exhaled. Trickles of blood seeped from the laceration, infusing the sweat. A battle is one moment, one heartbeat. Time matters not, for time exists only beyond the battle. Into deep night they fought, and further still. When Winter Wolves howled in the distance and glacial gusts rolled across the expanse, they did not stop. When her ten-time gashed limbs weighted heavy as oxen and her head agonized of exhaustion, they did not stop. Even when the faint yellow of false dawn appeared to the east, they did not stop. Roars and screams escaped her throat in the early morning, when her strikes did not accomplish death. The Linewalker, shirtless and covered in blood, panted with every step. At one point he rushed her, loosing a flurry of jabs and thrusts and stabs. Asukai, on the edge of collapse, willed strength into her limbs and dodged. And ducked and parried. When she escaped, bled and bruised, he fell to one knee, eyes wide, uncomprehending. She would have attacked then, charged him and bored her sword through his heart. It might have been the intrinsic knowledge that he would somehow fend her off, or simple exhaustion—beyond what her body could take—but Asukai's legs gave out. She knelt. Only her sword, embedded a few inches into the ground, kept her up. Ribbons of sunlight shone upon their bowed forms, casting long shadows to their right. She gazed at the golden clouds, severed by the sheer power of daybreak, and coughed a ragged, painful laugh. All night they had fought, an eternity and more. A thousand nips and nicks lined her body, as much as his, and still both of them lived. Both of them held on. Shichiro raised his bloodied brows at her, then chuckled, as if they shared an inside joke. For what might have been a few hours, neither of them moved. There is a darker side to a battle, darker than the blood and the maiming and the death. Deeper too, deep enough that most men, almost all men, never see it. Had she known it? I've known it my whole life, it birthed me, but I never understood it. Now she felt it. That pain, oh such pain. Not the one borne by the blade or the arrow, not what came at defeat or loss. You could slaughter hundreds, and not even see the shadow of this agony. But here she was, at the end, and the pain was no stranger anymore. To strike him down would take everything away from the queer, queer bond the night had forged, to strike him down would be surrender to that darker side. Their eyes found each other, red and black. Black and red. The knowledge, she saw, bloomed into his mind. A force unknown and unbent kept them staring at each other. Last, when all apprehension had died, Asukai rose. She donned her belt and sheathed the sword, then limped towards him, every step a torment. She needed a bath, a cold one to numb her muscles and joints, and a hot one to wash off the grime and sweat and dried blood and fresh blood. That would come later. She offered him a hand. "Let's go." "Where?" His voice was a rasp. His expression only half-confused. "Home." She did not know exactly what she meant by that, but they would find out eventually. He grasped her hand.  Soufyaan Timol lives in Mauritius and has published a couple of short stories in the yearly anthologies Collection Maurice. He aspires to be a writer and is currently working on an epic fantasy novel titled Killing Gods. He can be reached through his email address : [email protected] Poetry ~ Andrew C. Brown Seeking a solace When pennies drop how long until pounds of flesh are weighed. Quid pro quo only fair as loved ones die, revenge lightens dark rainbows. ~ Is this the world that we wish for? When war occurred, I wasn’t on guard. Detained through Logan’s Run decision. Concentration culled in camps alongside fellow-pensioners. New-age prisoners we had such fun, coughing up memories, daily gambling on death, playing roulette waiting for wheel to stop, winners declared, losing chips discarded. There is no more bingo sessions, no more shouts of House, the pensioners chorus silenced as bricks of society demolished, dismantled. ~ Self-isolation is not prison Self-isolation saves life. Lost freedom is Crown Court to waiting van. Handcuffed until secure in cubicle. (Do not know where I will be taken) Claustrophobic hot space suffocates any positive thought in mind. Other prisoners interact, dispense accusations, debate lenient sentences declare treachery. Knowing voices discuss tea options. I am the stranger. Three-year reality. Virgin stomach knots anticipation with fear. Think of those left behind whom I loved, betrayed. I told them two years. Van stops. Voices questions answers paperwork requested checked accepted. Gates open engine starts then silence. Released to laughing uniforms. Reception. Knew I had appointment booked. It was overdue. Must accept prescription dispensed. No wellbeing here. Plenty of pillars to hide behind or to be intimidated. Television plays familiar monotonous teatime fare. Conversations, sentences compared. Lenient courts. Curse my fate. Check other men. Feel I am scanned. Jeff Banks suit barcoded. Points me out as different. But I am not, I am like them all in this denial room. No stranger to addictive lifestyle voraciously dined on an unending, forever-famished gambling menu. Spot him immediately, 5’4”, big stomach, bushy beard, smartly dressed, paedophile surely. Thankful. He could be picked on before me hope do not share cell with him. Men called, men escorted, men processed, my turn, taken, with file and questions. Suit swopped. Non-entity clothing. I am given new identity, on database with my own assigned letters and numerals. Allowed telephone call, speak to crying daughter, explain where I am, try to be positive, say appealing against sentence, ask if she ok, tell her I love her. Don’t hear her reply. Allotted time expired. Returned to system. Trusted inmates serve anonymous food. Escorted to welcome of the wing, policed by Samaritan convicts. Ushered to new home, recognise newcomer on top bunk. Big stomach, bushy beard. Same clothes same letters, smaller number means he is always ahead of me in prison system. Hope he does not piss on me in snoring sleep. Reinforces headful of demons. I fire bullets executing misery despair destruction. Think of those I love. Try sleep. Fully awake on bottom bunk of locked prison cell. Tormented. Scared. ~ My ambition is just for today So much to complete. Finish given time. Recompense to pay. Invoice outstanding. Unexpected siren calls deceased abstinence. Reach ambulance. Recovery alarm triggered fight for virulence of life lived. ~ Epidemic of eternal, everlasting love You didn’t hear me at first, thought you were awake. Light glimpsed a chance to seep into the darkened bedroom. I watched you, asked again if you were awake. When you replied a shaky, stuttering yes, I asked could you turn over please? I had been ready but consciousness put a stop to my motions. As quick as I had felt the hardened possibility soft reality prevented more progress. You asked if I wanted to do my reading. I collected the small blue book from the shelf, brought it in amongst us, decided to share its daily truth, as usual, at half-eight. Our normal love-you exchange. I left warm bed. Dressed. Pyjama-clad. Collected charger. Descended to kitchen. Emptied dishwasher, carefully placed everything as it should be. Replenished fridge water dispenser, filled my normal glass. Topped kettle, prepared coffee, took one of the now-ripe Aldi green grapes bought the other day. (The red grapes were already ripe). Bargain carton for only a pound. Poured steaming liquid in red Nescafe mug. Glass, mug taken to lounge. Checked phone, placed it on charge. Opened laptop. Typed password. Completed random hard -level Spider Solitaire. Scored point less than my highest score. Felt another sniff. Earlier I had sneezed. We are both vulnerable. Windows Media Player. Headphones. Nearly half-eight. Final track heard before ascending to the bedroom. 1976 Album. Drought year. Never-forgotten assault. Fermented addiction. Sang each word perfectly. Pretended to play piano, Day at the Races track two - you take my breath away. ~  Andrew C Brown’s words draw on experiences as an addict, a prisoner and living on one of the most deprived estates in the UK. He achieved a community regeneration award for his work with offenders and their families in South Bristol as well as winning a Highly Commended Award in the national Koestler competition. His work has been published on three continents including in publications such as The International Times; Magma; Ink, Sweat and Tears; Sentinel Literary Quarterly; Lakeview International Journal; The Stray Branch. Short Fiction ~ Keltie Zubko “Hush,” he said, his hand bolting through the shadows made by the fire, to grip her face, cheekbone to cheekbone, and clamp down over her lips. “Don’t say that. Ever again.” “But…” she tried. He pressed his palm tighter across her mouth. She smelled sweat, tasted dirt with an underlying flavor of a pungent chemical, deep in his pores. Her tongue accidentally grazed his hand then withdrew to the back of her mouth, making her salivate, want to spit, but instead she fastened her lips against the taste. Her nose wrinkled, and she breathed in short gulps, trying to control them, but failing. He had succeeded in silencing her, that’s for sure, but not by his command. He must have remembered it wasn’t so easy just telling her to shut up. She concentrated and held still, listening. The dark pool of silence covering the undercurrent opened up by her words ebbed into a gentle hum of conversation like water closing over something heavy dropped into a deep well. Gradually, the flickering of the firelight across their faces and bodies, and those of the other huddling people around them became the only motion, and he relaxed his pressure. Autumn chill from the red dirt crept through her jeans to her legs and upward into her body as she sat there, waiting, jammed against him as if he were her other half. Hearts beat: hers, his, or the very earth that held them, she couldn’t tell, but felt a small backbone of resolve rising from this most familiar ground, this place, hard-packed from dirt bikes and hikers, dog-walkers and kids. It was just off the main path from their childhood haunts, where they had run boisterous and noisy through the summers and into the winters of their youth. Memory inched through her clothing, filthy now, through her legs, up into her torso to infuse her spine. She hadn’t expected him there. She thought she’d never see him again, though perhaps she should have heeded her own tales of the prodigal son, or the redemptive return of the wandering hero, or just the idea of a bad penny always turning up again. She’d known it was him the moment his silhouette blocked out the firelight where she’d made her lonely base for the night, in the company of travelers, vagabonds, deserters and soon-to-be exiles from this place, the park just down the hill and into the forest from her childhood home – and his. Is that what brought him back, that he’d heard of their eviction, wanted to see it – or her – one last time before they dispersed? She felt him ease the hold on her mouth a tiny amount, and she waited for her moment, considering. Should she fight him, get up and run? Should she sit in watchful silence? Obviously, given his reaction, there must be danger somewhere around them, that he could see and she could not. Wasn’t it enough that they were being forced from their tiny community that never bothered anyone? They hadn’t been cooperative, for sure, and perhaps she’d had something to do with that, but they hadn’t been trouble-makers, either. He would know that from his job. Her cheeks flushed, not from the fire, but questions she wanted to voice, considered, but squelched. It didn’t come naturally to her, but she had learned not to speak everything that occurred to her. Her fists clenched and she felt his arms tighten once more. The whole past and the whole future were told in minute gestures, not words. That, more than anything, brought tears to her eyes, but she blinked them away. Around them, the crowd settled in for a last damp night around the fires, forced to cluster together for body’s warmth, yet all the while holding a protective mental distance. Mist from the lake nearby rose to shroud and separate them from each other, a palpable cloak of doubt and suspicion, even though they had been neighbors and a community: relatives and friends, some for generations. That was before change had overtaken even them, in a relentless series of small, subtle increments. She had words for all that, but only in her mind, itemizing the chain of censorship from societal pressure through regulations and ostracizing, then criminality, and now, finally, lawful court-ordered biological intervention. No wonder that despite the closeness, there was distance between each of them. He had been raised on the same street as her from toddlerhood, lived only three houses away. Her mother’s mother’s generation would have said they were chums. She didn’t dare say even that, however, for any reference to the way things had once been was dicey, would likely be silenced in one way or another, just as he was silencing her now. Some ways of cutting out the words were more painful than others, and she needed no reminder that he had ended up being one of the silencers. She felt his palm loosen and instead of a muzzle, it took the shape of a cradle for her whole jaw, as if he himself felt the cramp he’d made in the muscles of her lower face by his gripping. The sudden withdrawal of his hold seemed like a tenderness, almost, but she still felt the ready tension in not just his hand and arm, but his whole body, pressed onto hers. She wondered what brought him back from the city to the now-deserted neighborhood, and what evoked this acknowledgement of their past childish friendship. But the shifting made her taste his filthy hand once again. She thought she could almost distinguish the flavors: dirt, blood, grease, sweat, and beneath those, something strange and bitter. But maybe she was just telling herself stories, again. She let out her breath and cautiously inhaled, realizing she’d been rationing her lung capacity in shallow gasps and fits. Now she smelled the sourness of his shirt, not the sweat of physical work, not remembered from their childhood, but that too-familiar stench from people nowadays, hiding and hovering in the shadows, people stepping in front of the outspoken, hushing precocious children or prattling elders. It was that smell she rebelled against taking into her lungs, ingesting into her soul. Why should he carry it on him, since he was after all, one of them, the enlightened, the powerful, given privileges for his work messing with their genes, manipulating and moderating rebellion. Why should he reek of it? She turned her head, firmly pulling away, forcing back his hand by will alone – or will and memory – until her gaze could rise upward to look into his face, his eyes, and as she did so, he tightened it across her mouth once more. She reached her own hands up to pry his away, but then his other arm reached around, constricting her shoulders even more, while he leaned his head to hers, putting his lips to her ear, whispering, “It’s okay, rest easy. I won’t hurt you. But just don’t speak. Don’t say that, ever again.” His body settled around her as if they had only one heart to beat, one set of lungs to breathe. In the dimness, she looked into his eyes. Despite everything, it was still him, her childhood pal, yet another old-fashioned, silly word. Was that the strategy, to get rid of the words, get rid of their history? She shuddered, deep inside, and he drew a part of his smelly jacket around her. Looking at him she saw he still had the same shaggy hair of decades ago, its color indeterminate now, but still unruly. She tried to relax her body and he let up the pressure on her jaw once more, but kept watching her. His face was grubby, but despite the fickle light that moved and diminished then flashed for an instant as the fire died and was stoked, crackled bright and faded, she could see remnants of that spark in his eyes buried amid the dirty crinkles of his face. They’d both aged, but the lines seemed too deep around his eyes. Maybe it was just grime and shadows, accentuating everything she noticed. She remembered him as a young boy, playing in the woods with her in that peculiar red-colored soil of the Pacific Northwest forest, made by the overbearing red cedars rotting to dust. They’d often rubbed it into their bodies, reddening their skin in some game of pretend, making themselves something she would never dare say. She still thought in the old vernacular, couldn’t help it; it was ingrained in her soul, just as the dirt had been ingrained in their skin. She shook her head, more like it was trembling, and he frowned at her. She could not even think without the old words. No wonder when she didn’t pay strict attention to each one of them and their implications, they popped out of her mouth, stopping conversations, making those silences, ready to burst like a match to black powder starting a conflagration beyond her intention or control. At this moment his face was intent, somewhat fearsome and she saw again that small child, growing like a flame from boyhood to youth. Her own face relaxed into a smile, despite the soreness from his paralyzing hold on her, despite everything. The fierceness of him! It was always a necessary part of the story, for what was a story without its hero or villain? He’d understood from the very beginning the role she needed him to play. He was the actor, as she had been the story teller. And he was without equal, the most adventuresome in their gang of hooligans, running from dawn to nightfall through the parks and paths by their homes, on their street, in the neighborhood, fashioning hideouts and forts in the woods, in their backyards beneath the over-arching cedar and fir, hemlock and giant maple. He built the weapons and tools, the props and the costumes, all in service of the story, whatever archetypal story she’d summoned for their pleasure in the long days of summer and childhood and sweet strawberry-scented air. Just as she was the keeper and the teller of the story, he had been its main character, villain or hero, actor willing to play the parts she’d given him. In those days, their parents let them run unsupervised and free. Her feet in their worn boots could almost feel bare again, cushioned on the springy moss, or scrambling, hardened over rock, diving into the cool lake surrounded by leafy woods. Together, they were a formidable team leading the rest of the children in their invented scenarios, culled from the old books, paper books, retold in their games, before the days of television, video games, YouTube, movies on demand, Netflix, and screens everywhere that blocked the sight of the tall trees against the sky, the lake and marsh, the mysterious paths veering up and down and around, the animals that crept past them in the night, the overgrown bushes drooping with lush berries that only they stopped to devour. He still didn’t trust her not to speak. She could feel it, as surely as if the censoring impulse came from her own body, still captive to his. His hand had loosened to cup her jaw again, but he kept it close, ready to stop up any words she might speak. She felt those long fingers, and saw them in her memory, growing strong and deft, past childhood then to adolescence, hands grown much too soon like a man’s: skinning a branch for a spear, or constructing shelters in the dry, August-parched dirt, tying fishing line, or reaching out to her from the water, acting out a rescue. With those clever hands, he could do anything. She had no doubt he was an excellent surgeon, extricating genes from the most recalcitrant specimen to splice, replant, experiment or destroy. She shuddered again. That was no laughing matter, imagining what those hands had gotten up to. She kept looking at him, trying to read his expression, any meaning he might convey with his eyes. Is that what they were reduced to? No words, at all? But still, she could read the tales of those long ago days, their childhood writ in images, a progression of charmed and boundless summers, and the plots she wove and he executed for their amusement. But then came the end. It wasn’t so much that they all grew up, but that they withdrew, each to their own warm house, to different companions, those more engaging picture screens. They all had electronic games to play – she did too. They drifted away, first one or two, then others, as technology supplanted the days of escapades in the woods, dipping into the lake, acting out whichever new game she devised. Finally, it was just the two of them, and she had to be even more inventive for the lack of supporting characters. She’d managed, for the ancient leather-bound, gilt-edged classics of her grandfather were full of stories with one or two main characters, fighting nature, fighting each other, fighting imaginary demons, or fighting their own souls. It wasn’t as much fun without the others to add steam and color to the project. They missed their company of actors, gone inside on rainy, winter days as well as those perfect moonlight-strewn summer nights. She didn’t remember if they’d mourned, or even talked about it, the end of that camaraderie. Did they notice the difference, that the videogames and movies were not the same to them, sitting there inside the houses, watching, instead of acting? She always wondered. He too left, going away to some great future, they all heard, while she stayed on in her parents’ house by the side of the park, in the old neighborhood. Now he was back. Embers from the fire glowed, also settling in for the night. Once in a while flames reached upward in a burst of pitch as a colony of sparks escaped, flying into the dark sky above the slumbering forms. She couldn’t tell if anyone was awake and listening. Meanwhile, they two breathed in uneasy harmony, resting for now in their own cocoon of memory. And then he said to her, so only she could hear, “You don’t know what heresy you speak. You don’t know the penalties. They are searching for those who carry your gene. It has a name, you know, and if they hear of you, they will steal it, suppress it, modify it. You will have no choice.” She sat in silence, staring at the tiny flames. In ages past, centuries ago, as well as just a few years back when her father took the neighborhood kids camping, groups of humans gathered around a fire such as this and told their tales. Many things had come from those stories, as well she knew. There were even legends about telling stories, and the consequences of that. If there really was such a gene, she surely had it, as her father had before her, as generations back to the beginnings of human history. His hand slipped away from her face now, to clasp her hands, warming them as he never had, back in those younger days. She watched his face, saw his eyes darken and felt the silence around the fire, except for sighs and groans and murmuring, and the crackle of it, an unanswered challenge that would die into lifeless black cinders if she did not speak. She reached her hands up to his head, smoothing the disobedient, boyish hair, then pulling him closer, his ear almost touching her lips, she whispered into it. “All I said was some old forgotten Hopi saying: ‘The one who tells the stories, rules the world.’” “I know,” he said. He pulled back from her and she saw water pooling in the corners of his eyes, glinting in the crinkles at the sides, overflowing and running down his dirty face. “I know.” “You never believed me, before.” “I do now.” “But why?” He did not answer. She looked up and saw in his face the shadow of all the stories she’d ever read, ever imagined, ever told. No, ‘shadow’ was not the right word. It was something more hopeful than that. Probably why he’d come back to find her. Not just to save her. “You don’t understand. You’ve been working for them too long.” He looked at her, shaking his head. She reached her own fingers up to the sides of his head, as if he were a small child again, placed a thumb at the corner of each eye, squished the moisture sprung from the red dirt in the creases. Her fingers made smudges there and she smiled, thinking of the war paint they’d made from the mud, as children. “You don’t understand,” she repeated, “It doesn’t matter if I say it or not. You know it’s true. My words don’t change it and all your science can’t, either. Believe it or not, I don’t care. They – you – can’t kill it, unless you kill us all, including yourself. Everyone has the story-teller’s gene.” ~  Keltie Zubko is a Western Canadian writer who lives on Vancouver Island. She has an extensive background in free speech/human rights legal cases but most likes writing about our human relationship with freedom and technology. Poetry ~ Chad Norman SURVIVAL: HERE I AM! for Nicoleta My foot in a favourite slipper taps just above the carpet installed years ago, across the room filled with the songs of Bad Co. making me cry, feel for the days I was 15. Here I am back with Mystery or am I moving ahead holding its hand not knowing a thing about the future, standing nonetheless on "Only", a place I was afraid of, standing though, only, only, only... Steps continue to be effective one, still after, one, how to be about survival, how I will survive again, moving still, an older man I want, an older thought of who he is, or, perhaps, an older me now ready for the newness I know nothing about. I see the bird feeder is being soiled. I revere the birds unafraid of the storm. Here I am, asking for nothing, with no hands brought to a prayer, here I am setting out to help the crows who always have an answer first. ~ WHERE THE PATH IS MELTING How quiet can a child be? Please, please, bury me with Hope Sandoval singing, "In To Dust" as the singer of Mazzy Star, as the world becomes more bizarre. How quiet can a man be? Thank you, thank you, hear me with only these words, my words, no famous singer, just me, saying these lines, just the world ignoring the poet. It is day now, so daylight talks, in among all the voice of Winter lodged where cold isn't a brute, but when I recall that child asking for so little when so little I love how much I don't know, I don't want to know. Done with the branches' strengths you come up the driveway with perfect legs, playing yourself through strings and power left to a song you know I know. The one left of where the pen sat, yes, over in the drawer you protect where the child & man have laughed over and over because life gives, of course, gives each one a bit of daylight and darkness. Something someone will find out in the middle of a field where snow drifts over old footprints. The melting path of all planning to leave homelands being bombed or lied to, taken from their children they believe Canada can help raise, can help to get to the other side where a piece of clear ground is found. No snow, no wind, no opposition to them simply hoping to stand and not slip on any wish to have them fall. ~ THE PROOF IS IN THE PUPPETEERS for Michael M. Beauty is also found in the arrival of darkness, I watched as the clouds became the new land and dear, rainy Glasgow disappeared beneath them, it was then I remembered my son, the one I don’t like to call step-son, the one I have heard say he loves me. And that has been enough throughout all the years we managed to stay alive here in a country where the news given to the public in all ways he now as a young man of 19 finds impossible to believe, a young man alive in times glutted with sources, sources he will not trust, a young man I sit and listen to, hearing his plight, hearing him asking for honesty, asking me to accept his pure mistrust, or is it distrust, or is it being lost? How many living-rooms are open for his calm, for him to sit and look at me, sitting in my beliefs about all of it, all of what I can say something about, so he has more than my face looking as searching as his. Just the sofa and chair there holding us for those moments when we were able to share not only opinions and vehemence but all the easy-to-discern lies we both were being fed, and unfortunately paying for in order for all of it to enter the room where we sat briefly, a room we grew up in, a room now filled with a world we knew was better than we heard, a world we knew to be the one being lied about, a room where my son was able to reveal his feelings brought about by a look in my eyes too, a look so vital we felt life very close, so close the talk faded into smiles. Humour is also heard in the departure of silence, I smiled thinking of Wales how much I had left there, most of the world’s strife and how I needed my wife, the woman who gave me him that far-away young man filled with all what he deals with daily. But the dismay right beside me, the load I know we both carried even though an ocean then was between us, was more than him and his young years, a load I will try to take from his shoulders, from his doubts I do not wish to see there any longer. A beauty and humour our lives will go on with, our chats cannot stop being chats, even though all of the world we hear about isn’t always the world where we try to live. There are strings attached to them, strings being agreeable in the hands of the puppeteers, old, too old, men dependent on the corporations they have misled for the benefits, for the lack of creative abilities on how and when to make their tugs, their pulls, on each string to somehow mean goodness for those they desire to swindle, and continue to leave my son without a direction, a quiet time where he could get behind the removal of anything I ever let set in my pointing eyes. Hope is also found in the whispers of the ones our bodies and doubts have made. The meaning of us, of all of it, in a photo, someone will find one soundless day, one, perhaps, in the future when the word people will always be chosen before migrant, immigrant, or even refugee. ~ MAKE-UP ARTIST FOR A NEIGHBOURHOOD STONE During the invasion of a virus throughout the smogless streets I am thankful to use my winter-gloved fingers to gladly wipe away a group of smaller stones someone not so hopeful chose to cover the larger stone there on the healing earth with a message saying, "Don't Worry", painted on it in yellow and left by some brilliant child, a hand I wish I could shake and hold onto until forever returns. ~  Chad Norman, Truro, NS, Canada His poems have appeared for the past 35 years in literary publications across Canada, as well as a number of other countries around the world. He hosts and organizes RiverWords: Poetry & Music Festival each year in Truro, NS., held at Riverfront Park, the 2nd Saturday of each July. In October 2016 he was invited by the Nordic Assn. for Canadian Studies to give talks on Canadian Poetry and read from his books at Borupgaard Gym in Copenhagen, and Risskov Gym in Aarhus, as well as other readings in both cities and Malmo, Sweden. Because of that tour Norman has started the manuscript, Counting Coins In Denmark And Sweden. His most recent books are Selected & New Poems, from Mosaic Press, and Waking Up On The Wrong Side of The Sky, from Grant Block Press, and a new book, Squall: Poems In The Voice Of Mary Shelley, is due out Spring 2020, from Guernica Editions. Recently, he completed the manuscript, The Black Rum Poems, and presently works on a new manuscript, A Small Matter of Inclusion. In October of 2017 he read at various Eastern Canada venues in Kingston, Ottawa, and Montreal. And in the Fall of 2018 Norman gave a speaking/reading tour of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, as a celebration of literacy and Canadian Poetry. He is currently a member of the Federation of NS Writers and The League Of Canadian Poets. His love of walks is endless. INHERITED RAGE My half-brother’s condition a consanguineous syndrome; (his blood Irish - veins Egyptian) We watched him on the footie pitch famous for that fifteen – throwing punches not footballs; Hooligan of the terrace De Niro of the estate. Our father played rugby expelled his mist against foes; afterwards hand - shakes and banter if he got caught by the captain’s blow. My own anger lay dormant awaiting to rise like my father’s – A brawler on Wetherspoon’s beer spilled floors like a bear rolling for food & cheap tricks; In time all reputations faltered I swapped my fists for words; even now the mist lingers like a trapped and raging animal - breaking out of human skin. ~ HOUSE ARREST Finding myself quarantined dividing energy between bouts of twitching legs feverish sweats of Anxomnia. I dream of feeling the sun taking a breath of our first incubated summer. What it must feel like to smell spring? bright flowers and the open bloom expectations are now of a high birth rate. Men dressed in pyjamas wear surgical masks glue toilet tissue to both hands - exhausting their frantic play stations. Incarcerated with one million home comforts - television repeats of old sit- coms; we see only a shortage in toilet rolls but not contraceptives. We twiddle our fingers play with our foreskins; wait for the cure to our anxiogenic future. ~ RESILIENCE We all clapped & felt a sense of well being if hope had found a face regardless of class It wasn’t the mask we were hiding behind but those simple emotions we had long forgot; The face that we see is one of resilience held between rocks that we split open on the beaches of tired men. We all clapped & death pondered human fragility & resolve the measure of our species; would see a world slumped like a drunk on a midnight bench; Would our future be an empty hour-glass? Held in the crumbling hands of delirious men lost inside the screenshots to an invisible shore. ~ THE VOYAGER Our final breath on earth the last time our names will ever be mentioned. (The Egyptians had told us that we die twice) we moved our celestial sat nav’s guiding us through tombs of the deceased; will they ever leave our souls in peace? Down office corridors filled with statues of hawk headed gods; do not scatter bones and ashes near kings & fellowships of obsequious fools. Let them swallow the guts of men leave me far from those voyagers & their cabal of perfidious dissidence. Let me drink wine with the sun god in a boat of silver heading to the underworld - may the judgements of our life - bare truths unhinged and treacherous. ~ Matt Duggan was born in Bristol 1971 and now lives in Newport, Wales with his partner Kelly. His poems have appeared in many journals including Potomac Review, Foxtrot Uniform, Dodging the Rain, Here Comes Everyone, Osiris Poetry Journal, The Blue Nib, The Poetry Village, The Journal, The Dawntreader, The High Window, The Ghost City Review, L’ Ephemere Review, Confluence, Marble and Polarity. In 2015, Matt won the Erbacce Prize for Poetry with his first full collection of poems Dystopia 38.10 (erbacce-press). Matt won the Into the Void Poetry Prize in 2017 with his poem, Elegy for Magdalene. Matt has previously published two chapbooks: One Million Tiny Cuts (Clare Song Birds Publishing House) and A Season in Another World (Thirty West Publishing House). In 2019 Matt was one of the winners of the Naji Naaman Literary Prize (Honours for Complete Works). His second full collection Woodworm (Hedgehog Poetry Press) was published in July 2019. Poetry ~ Rachel J Fenton Field Research When I go there, I am ten. I am forty-three, when I go there like playing hopscotch; I cast a thought back and skip all the way to the start. I went for real in November, and before that Spring – there behind the wire fencing, I’m in; the hole big enough to fit a saddle through. The earth, hard at any time of year. Galloping memory, I am ten again. Wearing big cousin’s new-to-me shoes, peach colour is soft contrast to the heels I dug into hard clay to get my footing, though they were the reason I’d been unable to run away from the two young men. Young but years older than me. Boys, the policeman described them, about to leave the school I was about to go to. The New Zealand lit scene is a playground. See? Like that, I cross oceans as well as the field. I have PTSD and my therapist sends me into my past like Knight Rider following a light from left to right; a Kit to get me in and home to Yorkshire, where definite article is as absent as my father and linguists come on field trips to research our language, and back to Aotearoa, to cauterise the trauma here. My therapist grounds me: You are in the present moment; you are safe now; how old are you? ~ Untitled It is written in my body before I write it. Already a page, earlier thoughts weighted like hoofprints in snow, lies on the bathroom floor. When I lean to touch it, crowns of water sink. I revel in the ink’s bleeding, distant rain from the mechanical cloud edge. I have been soaking for above three hours. From the wall beside me, a tap protrudes like the muzzle of my favourite hound, produces a convenient waterfall that can be used to curtain my thoughts from the body’s outer reality. It is in my nature to imagine things are not as they appear. And comfort takes many forms. Various outcomes materialise around me, I their Frida Kahlo; tender renderings of possibility appearing like imagery in a darkroom. But these cannot be lifted out to dry, pegged on a line or framed. As the only remembrance of tears is the taste of salt, so too the heart’s food leaves a bitterness though otherwise no trace. Listening now to the clever whispering of the fan, know I am reminded of the last words spoken by the mistress who for three years has hidden inside me, a hypocritical twin; the monotonous functionality, an annoying accompaniment I am only aware of in the instant after it is switched off. Drip, drip, drip. Like Alice Oswald’s “Swan”, I am lifting from the wreck myself. Unlike the dead bird, I have left the lead weight of the water’s skin. Hush. As the drips fold in on themselves like poisoned robes, I sing. ~ How to Care for Orchids Although it is winter, inside the glasshouse orchids in full bloom have sent long stems, like wash-lines hung with exquisite laundry such as only babies wear, ruffled with broderie anglaise trims, that curve as shoulders might from the weight. From the tops of tropical trees to English bogs and chalk downs, these are not flowers native to New Zealand, yet my friend’s daughter names each species with the care of a child writing her first party invitations. Her enthusiasm is endearing, her memory endures despite its encounters. Poisons occupy many forms and cuttings cannot insure against losses, even water given in too great quantities can kill; flood must be avoided in favour of letting these exotics take moisture from the air when left completely still. ~ Carnival of History Three magpies descend from high pine at the far end of the field. I want to feel; I call them family. Two parents, one child. But without proof they are as variable as the purpose of shame. How many times if a polecat could count; she returns to this field where her kit-self hid. She has come again to rescue her. She has gone to the place she was last seen. In her wild state, she was claw and teeth and dull fitch. In her winter prime, she gleams shiny as anger for what she has lost. That winter day you bore witness the stoats split from under the sleeper on your end of the crossing, their colouring an embodiment of snow on wood, as you watched, electrified, their sparking gambol over the road, jack and jill through the hole in the wire gate entering the field, their prints warranting execution. ~ You saw the mist first last night, called it fog, pointed out where it was forming around the old lampposts alongside the motorway driving back from early dinner with your friend, a softness that turned my thoughts to a dream I shared about a house shingled with the scales from moth wings. Write that down, you said. Now, I think of masked lapwings, the other name for spur-winged plover, and their downy brooding feathers gently tinged like winter sun, like lamp-light diffused through mist I cannot get near enough to touch. Mist appears solid but disappears from the place we should meet; I walk through it, empty as a promise. ~  Rachel J Fenton is a working-class writer from South Yorkshire, UK, now living in Aotearoa New Zealand. Her poems have appeared in English, The Rialto, Overland Journal, Magma, Landfall, and various anthologies. |

StrandsFiction~Poetry~Translations~Reviews~Interviews~Visual Arts Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed