|

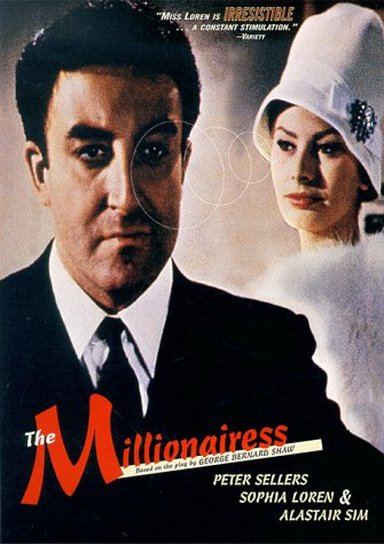

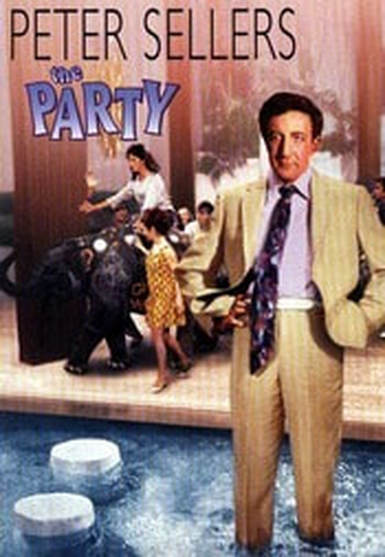

Film Review Hanif Kurieshi Here's an odd thing. As a mixed-race kid growing up in the south London suburbs in the 1960s, I liked any film starring Peter Sellers, particularly I'm All Right Jack, Dr Strangelove and The Pink Panther. But my two favourites were The Millionairess and The Party, both of which starred Peter Sellers as, respectively, an Indian doctor and a failing Indian actor. In both films Sellers, in brownface, performs a comic Indian accent along with a good deal of Indian head-waggling, exotic hand gesturing and babyish nonsense talk. He likes to mutter, for instance, "Birdy num-num," a phrase I still enjoy replicating while putting on my shoes. And I'm even fond of singing Goodness, Gracious Me, the promotional song from The Millionairess, produced by the peerless George Martin. So, at the end of the 1960s, my sister, mother and I came to adore Seller's Indian character, repeating his lines aloud as we went about our business in the house, because we liked to think he resembled Dad. My father, an Indian Muslim who had come to Britain at the end of the 1940s to study law, was, in his accent and choice of words, upper-middle-class Indian. As a child and young man he'd spoken mostly English since his father - who liked the British but hated colonialism - was a Colonel and doctor in the British Army. However, we didn't think of dad's accent as Indian: for us it was a mangling of English. There was a standard, southern, London accent, and he didn't have one. He was a mimic man, but a bad one, as all colonial subjects would have to be. If the white Englishman was the benchmark of humanity, almost everyone else would necessarily be a failed approximation. Dad could never get it right. Indians were, therefore, inevitably comic. And because my father, as a father, was powerful and paternal, our teasing shrank him a little. Dad was also sweet, funny and gentle, but not wildly dissimilar - in some moods - to the hapless character Sellers plays. My sister and I had been born in Britain after all. We knew how things went and Dad didn't. As I wrote in The Buddha of Suburbia, "He stumbled around the area as if he'd just got off the boat." If my father's way of misunderstanding hadn't been comic it might have become moving or even upsetting. When I got older, my younger self embarrassed me. I vowed not to look at those movies again. Foolishly, I'd allowed myself to be tricked into loving a grotesque construct, a racist reduction of my father and fellow countryman to a cretinous caricature, and I'd be advised to backtrack on my choices. Yet recently, re-watching the films, when I stopped weeping, my views changed once more, and I want to think about what I liked in them. My mother had married a coloured man in London in the early 1950s, at a time when one fear in the West was of unauthorized boundary crossing, or miscegenation. It was with miscegenation that the terror of racial difference was placed. Men of colour could not and should not be desired by white women, nor should they breed with them. People of whatever colour could only go with others of similar colour; otherwise some idea of purity would be defiled. Racial separation thus ensured the world remained uniform and stable. That way the most important thing - white wealth, privilege and power - would be sustained. Nor was the crime of 'crossing' trivial. We should not forget that Hollywood's Production Code banned miscegenation from the American cinema for thirty years. As children of a mixed-race background, though not particularly dark-skinned [I'd describe myself as 'brownish'] as children we were subject to some curiosity. People were worried for us because, surely, being neither one thing nor the other, we'd never have an ethnic home. We mongrels would linger forever in some kind of racial limbo. It would be a long time before we could enjoy being different. It is with this in mind that we should look at The Millionairess, while not forgetting that Sidney Webb, a close friend of Bernard Shaw - the author of The Millionairess - and a supporter of eugenics, warned that England was threatened by 'race deterioration.' I was surprised to read that Shaw himself wrote, "The only fundamental and possible socialism is the socialisation of the selective breeding of man." Despite this, we should consider how few mixed relationships were shown on screen. Anthony Asquith's movie, made in 1958, was adapted by Wolf Mankowitz from Shaw's 1936 play in which the male lead is Egyptian. In Asquith's version, a divine Sophia Loren - an aristocratic, rich Italian called Epifania Parerga - falls in love, while attempting suicide, with an Indian Muslim doctor who, at first, sees her as nothing but a nuisance. I must have seen this on television, and I don't recall many people of colour appearing in the movies I saw at the cinema with my father, except for Zulu and Lawrence of Arabia. This was also a time when black filmmakers were virtually invisible. Not only is Dr. Ahmed el Kabir a Muslim man of colour and voluntarily poor, he is cultured, educated and dedicated to helping the indigent and racially marginalised. Most natives in most movies, of course, had always been shown as thieves, servants or whores, or as effeminate Asiatics. We were always considered dodgy. Roger Scruton writes in England: An Elegy, "The empire was acquired by roving adventurers and merchants who, trading with natives whom they could not or would not trust..." We were thrilled, then, that the movie would include no covert fantasy of coloured men raping white women, a trope which seemed to me to be almost compulsory since A Passage to India and The Raj Quartet. And The Millionairess does, in fact, have a nice Hollywood ending, with the mixed-race couple together enjoying one another. While the Millionairess looks creaky and silly in places, but is saved by the performances of the leading couple, The Party is a lovely film. Sellers, obviously a great comic actor, is at the peak of his mad inventiveness, and Blake Edwards is a brilliant director of physical comedy. Composed of a series of perfectly judged vignettes - a carousel of increasingly bizarre incidents -the movie becomes riotously anarchic as Sellers' innocent Indian creates, inadvertently, total chaos at the house of film producer General Clutterbuck, to whose party he is mistakenly invited after blowing up his movie set. At the beginning of the movie, Seller's character Hrundi is shown playing the sitar, reminding us that at this time - it is the year when Sgt Pepper was being played in every shop, party and house you visited - Indians were supposed to possess innate wisdom, beyond the new materialism of this dawning vulgar age in the West. When, soon after, Hrundi attends the smart Hollywood party, it isn't difficult to identify with his apprehension. Don't we all feel, when going to a party, that we are about to lose our shoe in a water feature and will spend the next hour on one leg? Yet he is even more out of place than even we would be, and unnerving in his strange, formal politeness. "Do you speak Hindustani?" he asks strangers, who are baffled by his question. "Could you ever understand me?" would be a translation. "Do you want to?" The Party was released in 1968 and I'm surprised at my enthusiasm for it at the time, since this was also the year of Enoch Powell's grand guignol 'Rivers of Blood' speech. If my father and other Asian incomers seemed wounded in Britain, vulnerable, liable to abuse, looked down on, patronized, tolerant of insults, racism made me want to be tougher than my father. My generation would rather resemble the black panthers than the pink panther. We knew we didn't have to cringe and take it, for this was the era of Eldridge Cleaver, Stokely Carmichael and Angela Davis. These blacks were so sexy with their guns and open shirts and attitude, and I'd been mesmerised by the black-gloved salute of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico Olympics. There's nothing macho about Hrundi. He's a different sort of heterosexual leading man to those usually preferred in the American cinema. When, at the party, he meets one of his heroes - a tough but charming cowboy with an iron handshake and a movie reputation for shooting red Indians - Hrundi is offensively absurd in his sycophancy. Yet there is something to his softness. The other men in the film, those involved in the film industry, are shown to be somewhat brutal if not summary with women, whom they patronize and infantilize. Hrundi is different. Perhaps women and people of colour occupy a similar position in the psyche of the overmen, which is why his friendship with a coy French girl [Claudine Longet] who sings like Juliet Greco, is so touching. The woman and the Indian, both subject to the description of the other, the brown man coming from 'the dark continent' and the woman as 'the dark continent', can recognise one another as supposedly inferior. Both are assumed to be inherently childish. As it happens, there's more to Hrundi's idiocy than pure idiocy. He seems like someone who could never be integrated anywhere. And his gentle foolishness and naiveté becomes a powerful weapon. If you've been humiliated and excluded you could become a black panther or, later, join Isis, taking revenge on everyone who has suppressed and humiliated you. Or you could give up on the idea of retaliation altogether. You could perplex the paradigm with your indecipherability and live in the gaps. After all, who are you really? Not even you can know. When it comes to colonialism, the man of colour is always pretending for the white man: pretending not to hate him and pretending not to want to kill him. In a way, Sellers' baffling brownface is perfect. And in some sense, we are all pretending - if only that we are men or women. Eventually Sellers' useful imp escapes the power and leads a rebellion. Or, rather an invasion in the home of the white master, involving an elephant, a small army of young neighbours and the whole of the frivolous Sixties. The swimming pool fills with foamy bubbles into which people disappear, until no one knows who is who. In a carnivalistic chaos they all swim in the same water. At the end of the movie, he and the French girl leave in his absurd little car. In both films, the Sellers' character knows he has to be saved by a woman. And he is. Significantly, it is a white woman. Walk out tonight into the city portrayed in The Millionairess and you will see the great energy of multi-racialism and mixing, an open, experimental London, with most living here having some loyalty to the idea that something unique, free and tolerant has been created, despite Thatcherism. Out of the two films, The Millionairess looks the least dated since its divides have returned. It has been said that Muslims were fools for adhering to an extreme irrational creed, when the mad and revolutionary creed, all along, was that of Sophia Loren's family: extreme, neo-liberal capitalism and wealth accumulation, creating the Dickensian division in which we still live. Equality does not exist here. This city's prosperity is more unevenly distributed than at any period in my life-time, and the poor are dispersed and disenfranched. Not only does our city burst with rich Italians and many millionaires patronizing urchins and the underprivileged, but a doctor committed to serving the financially excluded would be busy. London has reverted to a pre-1960s binary: a city of ghosts simultaneously alive and dead, of almost unnoticed refugees, asylum seekers, servants and those who need to be hidden, while many rightists have reverted to the idea that white cultural superiority is integral to European identity. Since those two films with their brownfaced hero, we have a new racism, located around religion. And today the stranger will still be a stranger, one who disturbs and worries. Those who have come for work or freedom can find themselves blamed for all manner of absurd ills. As under colonialism, they are still expected to adapt to the ruling values - now called 'British' - and they, as expected, will always fail. However, if the Peter Sellers' character begins by mimicking whiteness, he does, by the end of both films, find an excellent way of forging a bond with his rulers, and of outwitting them. If the West began to exoticise the East in a new way in the Sixties, the Sellers' character can benefit from this. For the one thing the women played by Sophia Loren and Claudine Longet lack and desire is a touch of the exotic and mysterious. It becomes Sellers' mission to provide this touch. For Akbir and Hrundi, the entry into love is the door into the ruling white world of status and privilege. To exist in the West the man of colour must become, as Fanon would put it, worthy of a white woman's love. A woman of colour has little social value, but a white woman is a prize who can become the man's ticket to ride. By way of her, being loved like a white man, he can slip into the west, where, alongside her, he will be regarded differently. Perhaps he will disappear; but maybe he will alter things, or even subvert them, a little, and their children will either be reviled or, out of anger, alter the world. A Hollywood ending tells us love must be our final destination. Yet there is more complexity to these lovely finalities than either film can quite see or acknowledge. Birdy num-num indeed. ~ Also published in Sight&Sound (BFI) October 2017 issue.  Hanif Kureishi was born in Kent and read philosophy at King’s College, London. In 1981 he won the George Devine Award for his plays Outskirts and Borderline and the following year became writer in residence at the Royal Court Theatre, London. His 1984 screenplay for the film My Beautiful Laundrette was nominated for an Oscar. He also wrote the screenplays of Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987) and London Kills Me (1991). His short story ‘My Son the Fanatic’ was adapted as a film in 1998. Kureishi’s screenplays for The Mother in 2003 and Venus (2006) were both directed by Roger Michell. A screenplay adapted from Kureishi's novel The Black Album was published in 2009. The Buddha of Suburbia (1990) won the Whitbread Prize for Best First Novel and was produced as a four-part drama for the BBC in 1993. His second novel was The Black Album (1995). The next, Intimacy (1998), was adapted as a film in 2001, winning the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film festival. Gabriel’s Gift was published in 2001, Something to Tell You in 2008, The Last Word in 2014 and The Nothing in 2017 His first collection of short stories, Love in a Blue Time, appeared in 1997, followed by Midnight All Day (1999) and The Body (2002). These all appear in his Collected Stories(2010), together with eight new stories. His collection of stories and essays Love + Hate was published by Faber & Faber in 2015. He has also written non-fiction, including the essay collections Dreaming and Scheming: Reflections on Writing and Politics (2002) and The Word and the Bomb (2005). The memoir My Ear at his Heart: Reading my Father appeared in 2004. Hanif Kureishi was awarded the C.B.E. for his services to literature, and the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts des Lettres in France. His works have been translated into 36 languages.

4 Comments

12/19/2018 12:07:27 am

Never read this website before.. strands that is... I am going to spend my holidays reading as many articles as possible. It's brilliant!

Reply

Marc Ramirez

3/27/2021 10:53:50 am

Thank you for this!

Reply

5/16/2022 01:03:46 pm

Insightful, conscious with much gravity in your illuminating questions and arguments. Thank you.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

StrandsFiction~Poetry~Translations~Reviews~Interviews~Visual Arts Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed